I’m not a fucking idiot — That’s what I thought while looking at the sign hung from the door of my hotel room in Đà Nẵng.

The sign reads:

Here on Son Tra Peninsula, a natural reserve area, you may encounter some of our friendly neighbourhood residents - Monkeys. However, we suggest caution:

- Please keep your windows and doors closed.

- Please keep your distance from the monkeys.

- Please do not feed the monkeys.

- Please do not leave your personal belongings outside unattended.

I understand the importance of not interacting with local wildlife and not acclimating the animals to human food and proximity. But it seems I’m not as responsible as I thought.

While sipping my morning coffee on my room’s balcony, marveling at the sea stretching out beneath tatters of clouds like torn cushion cotton, I heard two resonant thumps behind me, followed by frenzied scurrying. Bolder than I’d expected them to behave, two monkeys had leaped down from an overhanging tree and sprinted right behind my back into my room where they bounded atop my bed. Without breaking eye contact they proceeded to eat an entire plate of complimentary desserts. When finished, one lounged on the pillows while the other retreated deeper into the room and emerged with a canister of potato chips that she proceeded to eat on a balcony overhang out of reach but in sight of me. Uninterested in trying to chase the remaining monkey out of the confined space, I had to scramble down, half-naked, from the villa roof and seek assistance. When I returned to the room with a hotel staff member, the only sign of the monkey invasion was a cascade of rainbow-colored macaroon crumbs and smeared cheesecake frosting on the comforter.

Photos by monkeyhaven via Wikimedia Commons.

I’m a slow learner, and this was not my last run-in with monkeys here in Vietnam. On a visit to Cần Giờ, a monkey snatched my friend’s bag right off her shoulders. Unfortunately, it contained the only set of keys to her motorbike. The rapscallion primate scurried to the edge of the forest, sat down and stared at us. I once again over-estimated my intelligence and thought I could outsmart the monkey by tossing a bag of snacks which would prompt it to drop the precious bag to pick up the chips. No. It simply walked over to the chips while still holding the backpack. It thus had both chips and prized bag. Thankfully, an altruistic man who seemed to have experience with the monkey scofflaws arrived wielding a giant stick which he used to compel it to drop the bag (the chips, alas, were never recovered).

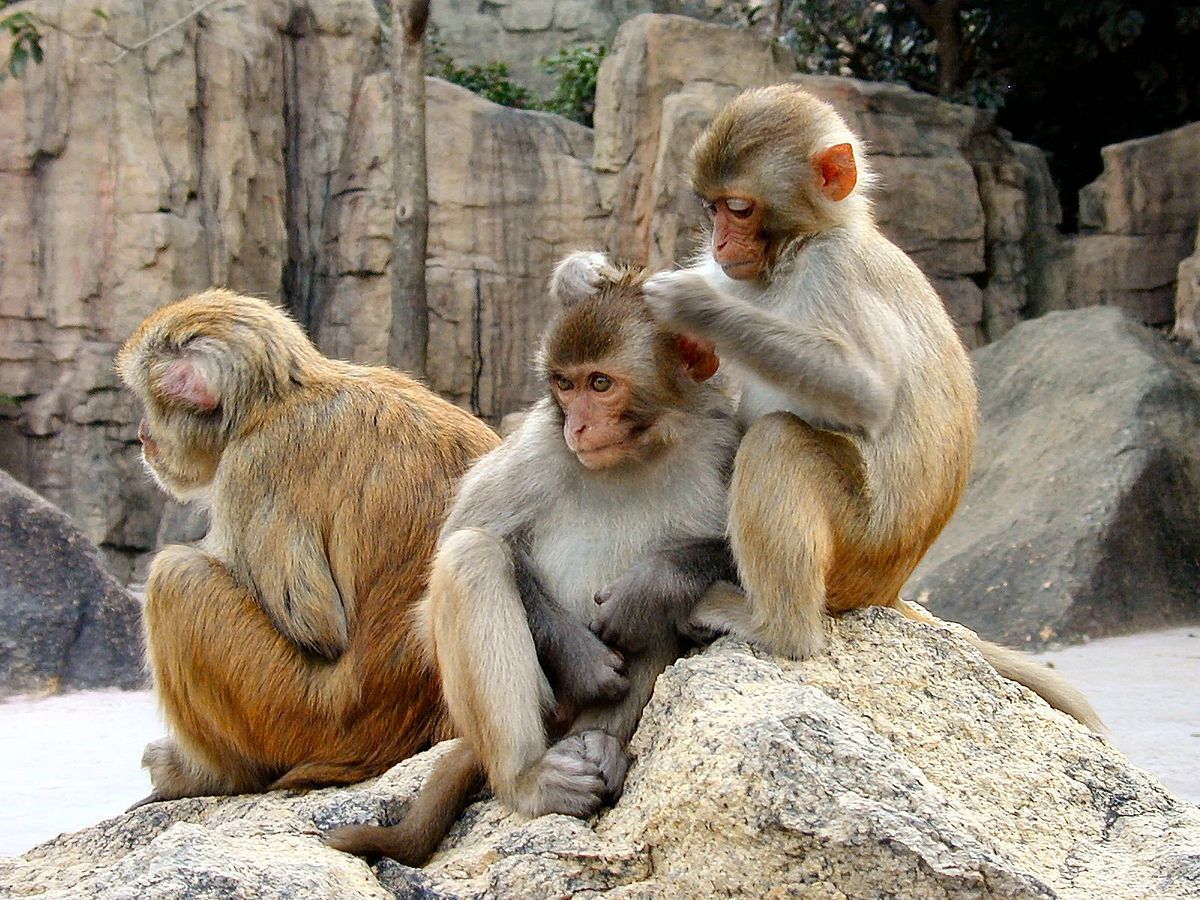

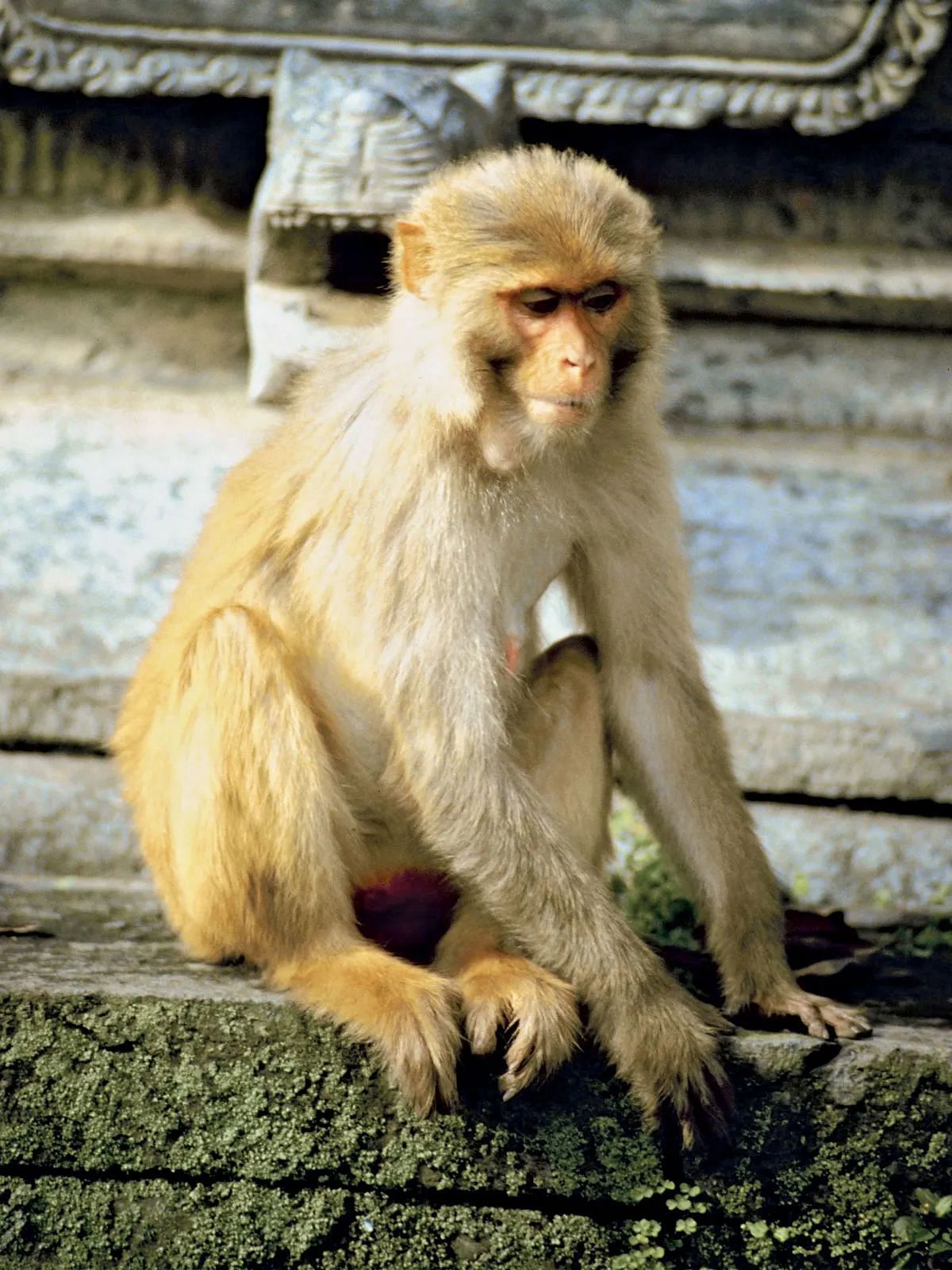

In both instances, the specific monkey were likely rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), one of the world’s most widespread and onerous primates. They tend to live in large groups of 30–50 individuals ruled by strict material lines. They are opportunistic feeders, typically eating fruits, nuts, leaves and insects, depending on what is available in their environments. Found across South and Southeast Asia, they are indigenous to northern Vietnam and the Central Highlands, but colonies have adapted to other areas throughout the country including in Cần Giờ, Cát Tiên National Park and Rều Island off the coast of Hạ Long City as well as established stable populations in the Americas. In Vietnamese, they are commonly referred to as khỉ vàng, not because of the color of their hair, which is a rather drab brown and sand hue, but because of their value when caught and kept captive.

Photos by Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

When you picture a monkey being used for research science, it is very likely a khỉ vàng.

When you picture a monkey being used for research science, it is very likely a khỉ vàng. They are the world’s preferred non-human primate for study thanks to their ease of captive care and the fact that they share 93% of their genes with humans. They’ve been instrumental in developing and producing vaccines for diseases such as polio, hepatitis A, rabies and drugs used against COVD-19 and AIDS here and abroad. In Vietnam, they are also occasionally kept as pets in private homes, businesses and even circus attractions that were thankfully shuttered in recent years because of intrinsic abuse. Their conservation status is listed as “of least concern,” and while research is incomplete, they are not in a precarious position like many other primate species in Vietnam.

I’m hardly the only one to have had run-ins with a rabble-rousing khỉ vàng here. Local media is littered with reports of the monkeys ransacking homes, attacking innocent people and generally causing havoc. And almost everyone I know has some story about monkey molestation that contributes to the consensus that khỉ vàng are menaces. They are particularly pest-like at tourism sites around the country where natural or once-natural areas butt up against attractions. Humans are far too helpful in teaching them that human food is both delicious and easily obtained from trash bags, unlocked homes, vehicles and even hands. In some instances, one could possibly defend the monkeys' behavior by reminding people that they are encroaching on their home territory, but in southern Vietnam where they have been introduced, they are non-native interlopers. If any animal deserves to be deemed an unrepentant asshole, its khỉ vàng.

Unlike many other native plants and animals such as thạch sùng, đom đóm and lêkima, khỉ vàng don’t often appear in Vietnamese myths, literature or contemporary culture (I sincerely doubt anyone will ever propose a Miss Vietnam costume modeled after those mangy mongrels, for example). I’m willing to guess their absence from pop culture is due to the fact that no one who has encountered a khỉ vàng wants to be reminded of them when listening to their favorite songs or looking at their favorite paintings.

Photos by Barry Lewis via Getty Images, Psychology Wiki, Britannica.

Rhesus macaques are aggressive, cruel, calculating and perpetually stressed out.

Rhesus macaques are aggressive, cruel, calculating and perpetually stressed out. Their rigid hierarchies rely on and promote transactional relationships and order maintained through threats of violence. Success, in the form of survival and passing on their genes, necessitates duplicity and abuse. Perhaps the most troubling aspect of macaques isn’t their behavior, however, but how closely it mirrors human’s. Xenophobia, gluttony, thievery, the use of deception to get ahead, preying on the most vulnerable on the social ladder and a penchant for colonizing new lands at the expense of native species; khỉ vàng embody the worst elements of mankind.

Perhaps, this isn’t so surprising considering we share a not-so-distant ancestor and have spent significant effort as societies to establish religions, customs and traditions to keep our khỉ vàng-esque instincts in check. Yet, I question anyone who witnesses the villainous mayhem found in any khỉ vàng community and doesn’t then recoil at the people they are surrounded by as well as the person they know lurks within.

But thankfully, humans and khỉ vàng differ in several profound ways. Researchers have made shocking claims regarding the inability of khỉ vàng to express if not experience joy. Moreover, their societal arrangements have discouraged the formation of complex communication that supports much more than threats or submissions. They cannot tell stories, for example. But humans can, so please allow me to share one:

After those two khỉ vàng ransacked my room, I fell into a sour mood. I was angry at the natural order of the world and dismayed by the conniving urges of our next-of-kin and, by extension, the treachery all humans are tempted by. That night, as I sat in my room atop a thankfully changed bedspread, I heard a rustle in the trees. I peeked out my window expecting to see another pack of marauding khỉ vàng the likes of which I had encountered numerous times throughout the day. But instead of the scrawny, scab and wound-speckled monkeys, I was gifted with a family of graceful red-shanked douc (voọc chà vá chân nâu). An entire family of the endangered leaf-nibblers proceeded to perch peacefully a few meters from my balcony.

Their calm demeanor, deep and seemingly ruminative gazes and zen-like presence stands at stark contrast to the khỉ vàng in nearly every way. They moved slowly pulled at branches without so much as a grunt or yell, let alone the unceasing screeches one hears from a group of khỉ vàng. They showed no interest in my room and only occasionally looked in my direction to assess if I was a threat. A mother douc held a child against her chest as she wove through the leaves and not once did I see her steal the little one’s food as is widely reported to happen amongst the dastardly khỉ vàng. And when they were done feeding and ready to roost for the night, they silently moved up the mountain, the trees rustling in their wake and gradually growing silent like a temple bell struck to invite prayer.

If humans often behave like khỉ vàng, we also certainly have the ability to behave like red-shanked douc, do we not?

Photo via Người đưa tin.