While Southeast Asia is known as one of the world’s fastest-growing economic regions, home to booming metropolises like Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City and Kuala Lumpur, it also hosts some of the planet’s most vital ecological areas.

The Greater Mekong, which includes Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Myanmar, is key to this environmental vitality. According to the WWF, more than 2,200 new vertebrate and vascular plant species have been discovered in the region since 1997.

In the 1970s it was the most densely forested area on Earth. Since then, a third of that tree cover has been lost. Another third is expected to disappear by 2030. Urbanization, land use changes and agribusiness such as palm oil and rubber have devastated forests, along with the wildlife species which rely on them for habitat.

The Greater Mekong is also home to one of the world’s major mangrove forest distributions, along with Central America and the southern United States, as well as the coastal tropics of West and East Africa.

Threats to the Greater Mekong’s mangroves

Mangroves live in brackish or saltwater, and Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar, which have more than 8,400 kilometers (5,200 miles) of coastline, feature significant forests of these trees. Cambodia, with 443 kilometers (275 miles) of coastline, has a mangrove area as well, though it has been seriously degraded. This is not uncommon.

Benno Böer, chief of natural sciences at UNESCO’s office in Bangkok, explained by phone that mangrove forests are largely shrinking everywhere they are found, with the exception of Eritrea, Abu Dhabi and Australia.

A typical mangrove forest in Panama. Image by Rhett A. Butler/Mongabay.

“The main reason approximately 32 million hectares [320,000 square kilometers, or 123,550 square miles] of mangroves globally have been brought down to 15 million hectares [150,000 square kilometers, or 57,900 square miles] is land use change,” Böer said. This decline has occurred over the last 50 years. “That includes agricultural development, that includes the establishment of shrimp farms and other coastal development projects.”

According to UNESCO, within the Greater Mekong region, Myanmar contains the largest area of mangroves, covering 5,030 square kilometers (1,942 square miles), followed by Thailand with 2,484 square kilometers (959 square miles), Vietnam with 1,057 square kilometers (408 square miles), and Cambodia with 728 square kilometers (281 square miles).

Forest destruction and degradation due to household fuelwood collection is an issue globally, including in Myanmar.

Piles of wood can be seen at villagers surrounding Mein-ma-hla Kyun Wildlife Sanctuary (MKWS) in Myanmar. Photo by Ann Wang

Three major intact mangrove areas are located in Vietnam, Thailand and Myanmar. In southern Vietnam, the 750-square-kilometer (290-square-mile) Can Gio Biosphere Reserve lies outside Ho Chi Minh City. The 300-square-kilometer (116-square-mile) Ranong Biosphere Reserve is in Thailand, just below Myanmar’s southern tip on the Kra Isthumus. Myanmar features a mangrove forest in the area between Kawthaung and Myeik, north of Ranong.

Böer said he recently visited Ranong and Myeik along with experts and policymakers from Myanmar, Thailand and international conservation organizations. The study tour was put together by the Manfred Hermsen Stiftung Foundation, Fauna and Flora International, UNESCO and the Mangrove Action Project. It examined the effectiveness of Thailand’s biosphere reserve and what lessons can be applied to Myanmar’s mangroves, with officials from the latter country expected to push for more protection of these areas as a result.

“The cutting of mangrove forests and converting the wood into charcoal is an issue,” Böer said. “Thailand used to lose a lot of mangrove due to woodcutting some decades ago. Then, they established a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and they had to have very transparent management plans, and those plans included the strict ban of mangroves being cut anymore.”

Mangrove forests are an important source of fish for the indigenous communities. Image courtesy of the Rainforest Foundation.

Mangroves were replanted in this area, and the specialists on the trip found that the forests have recovered well, at least in terms of biomass. However, this has pushed charcoal production across the border into Myanmar. This part of the country does not have a protected area. The Irrawaddy Delta, which also has mangroves, is home to the Meinmahla Kyun Wildlife Reserve. However, due to endemic corruption in Southeast Asia, the creation of a protected area does not necessarily mean all illegal activity will stop.

“The issue is that the illegal charcoal production in Myanmar has increased since charcoal production from the mangroves in Thailand has ended,” Böer said. “They are trading the charcoal from Myanmar into Thailand. It is now important for the two counties to work jointly on developing and applying professional transboundary mangrove management plans.”

Last year a Myanmar Times investigation found that charcoal production was on the rise in Myeik, with the product being shipped to cities in Myanmar, as well as illegally exported to Thailand in unrecorded quantities.

What mangroves do

Mangrove deforestation is particularly devastating given the vital ecological role these forests play for surrounding communities.

“Forests, in general, tend to be underappreciated for the many contributions that they make to human well-being across scales,” said Frances Seymour, a distinguished senior fellow at the World Resources Institute, via Skype. “But mangrove forests, in particular, serve a variety of functions that are underappreciated and that are disproportionately important both to local communities and at the global scale.”

Seymour, who authored the 2016 book “Why Forests? Why Now?: The Science, Economics, and Politics of Tropical Forests and Climate Change,” described the role of mangroves as a trifecta of human-nature interconnectedness. They support local livelihoods through fishing and the collection of fuelwood (albeit often illegally), act as nurseries for fish to sustain coastal fishing communities, and excel at storing carbon.

Additionally, they help to prevent flooding caused by coastal storms, which are expected to increase in severity and frequency due to climate change.

Florida mangroves. Image by Wilen Bill, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

According to Seymour, mangroves also combat tsunamis, “because of their function in coastal protection and attenuating the strength of wave action as waves crash into the shore.” While tsunamis are very rare in the Greater Mekong, research has found that mangroves in nearby Indonesia helped protect coastal communities from the catastrophic 2004 Boxing Day tsunami.

These forests play a huge role in mitigating effects of climate change as well, Seymour said: “They store a large amount of carbon and, like peat swamps, because they provide an anaerobic environment where organic matter doesn’t completely decay underwater without oxygen, you have carbon that is not only stored in the vegetation of a mangrove swamp, but also stuck in the mud, so to speak.”

Such functions are particularly vital in the Greater Mekong, where climate change is expected to severely impact coastal regions and major cities. Vietnam, for example, faces threats from both rising sea levels and more frequent typhoons. Both Thailand and Myanmar have experienced devastating flooding in recent years thanks to extreme rain events and storms.

An example of what is lost when mangroves are deforested can be found in Myanmar’s Irrawaddy Delta.

Charlotte Nivollet, Southeast Asia regional director at the Group for the Environment, Renewable Energy and Solidarity (GERES), said that historically the delta was a major charcoal production area.

The dense mangrove forest of the Mangrove Marine Park provide cover. Photo by William Clowes for Mongabay.

“This seems to be decreasing a lot simply because there is no more mangrove,” Nivollet said by phone from Phnom Penh, Cambodia. “In 2008, Cyclone Nargis destroyed most of the remaining poor, degraded mangrove out there, so it was really catastrophic.”

This storm served to highlight the role mangroves play in protecting communities from storms. “The effects of Nargis were even worse thanks to the fact there wasn’t much mangrove already, and it destroyed the rest,” Nivollet added.

Nargis was the deadliest natural disaster in Myanmar’s history, causing at least 138,000 deaths. According to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), when the cyclone made landfall the delta featured less than half of the mangroves present 30 years prior, when these forests spanned more than 1,000 square kilometers (386 square miles).

Methods to maintain mangroves

Fuelwood and charcoal are main focal points of GERES’s work in Cambodia, though Nivollet said charcoal producers have largely moved away from the country’s small remaining mangrove forests north of Sihanoukville, a beach city undergoing explosive, unchecked growth through massive Chinese investment.

“The mangrove has been very degraded over the past decades, for charcoal production and for other reasons,” she said. Now, most charcoal production in Cambodia takes place in the Cardamom Mountains, along the country’s border with Thailand.

While fuelwood production no longer appears to be a significant threat to Cambodia’s limited remaining mangroves, GERES is working on a pilot scheme for fuelwood production that could serve as a model in countries like Myanmar, which are struggling to maintain their mangrove forests.

“The laws and regulations are in place in Cambodia, but the thing is that the practical way of how to implement and comply with the regulations doesn’t exist,” Nivollet said. She and her team hope to create a sustainable charcoal value chain in line with regulations.

The first step would be to create the actual documents needed to comply with these regulations.

“We’re helping the forestry administration to develop from scratch the documents and letters that need to be obtained [by charcoal producers] — none of this exists,” she said. “There are many regulations, everything is clear on paper, but in fact it has never been implemented by anyone. Even the forestry administration people have no idea how to respect the law, so of course they can’t enforce it.”

Nivollet’s vision is for people living in community forest areas to produce firewood through sustainable forest management practices. They can then sell the wood to registered, fully legal charcoal producers, thus regulating and legally enforcing a trade that GERES estimates is worth $100 million annually.

The problem they are encountering is that applying to become a legal producer involves paying numerous royalties, fees and permit costs, disincentivizing the process of becoming legitimate.

“We’re trying to explain to the forest administration, ‘How do you want this sector to become regulated if regulations mean a reduction of the profitability for producers?’” Nivollet said. “It’s very challenging to find the way to make it profitable to produce sustainable, legal charcoal.”

While there is a long way to go in terms of achieving these goals, starting at the first step of creating actual legal documents, and similar regulatory issues exist in every Greater Mekong country, GERES’s strategy points to one way toward better forest management.

Another possibility is artificial mangroves, which UNESCO’s Böer says have been successfully tested in Qatar. “Some years ago we developed a system to grow mangroves in a sand-filled container with a semi-permeable membrane underneath which allows seawater to penetrate, but the sand does not fall out of the container,” he said. “Under the seawater we put an air bubble, which allows the mangroves to float on the ocean surface.”

UNESCO hopes to test this system in Myanmar, the Philippines and Australia in the future before expanding it further. “We want to suggest the establishment of floating artificial mangroves so that people can be encouraged to use these mangroves for the legal harvest of [fuel wood from] artificially produced mangroves, and then that can turn away from the illegal production of charcoal in natural mangroves,” Böer said.

Such a development is still in the very early stages, however. While the trial in Qatar was a success, funding has not been secured to expand the technology to other mangrove regions. Research is also underway to determine the financial costs and scalability of floating mangroves.

For example, UNESCO is currently working with the University of New South Wales in Sydney to test the seaworthiness of floating mangrove plantations, which would likely be placed next to existing mangrove forests.

Mangrove forest at MSN island in Myanmar, where groups hope to use the land as an educational center and nursing ground for various mangroves species. Photo by Ann Wang for Mongabay.

The future for the Greater Mekong’s mangroves

While such technical and legal advancements offer hope, there is little doubt that the near future will be challenging for the region’s mangroves, much like forests in general.

“Each country in this region is trying to keep double-digit growth, so they have to look at how the economy grows, and sometimes it’s about investment in land and increasing productivity,” said Thibault Ledecq, regional forest coordinator at the WWF’s Greater Mekong Program in Phnom Penh, in a Skype call.

“Infrastructure and agribusiness will continue to be major drivers of deforestation, and wood consumption is only increasing year after year,” he said.

One relatively bright spot, at least in terms of mangrove protection, is Vietnam. Though the Can Gio Biosphere Reserve is located within the limits of fast-growing Ho Chi Minh City, it has thus far been spared from the city’s rapid urbanization. Major tourism developments have been proposed on its fringes, but as of now it provides a striking green contrast to the nearby urban sprawl on satellite images.

“Several years ago, Vietnam began carrying out several programs for the rehabilitation of mangroves for coastal protection, while at the same time improving awareness among local people,” Pham Trong Thinh, director of the Southern Sub-Forest Inventory and Planning Institute in Ho Chi Minh City, said in an email. “Illegal logging in mangrove forests and wetlands is not a big problem in Vietnam at the moment.”

Vietnam’s mangroves are aided by the fact that the government has successfully provided a stable electricity supply to more than 99 percent of the country’s population, according to the World Bank. This means very few people need firewood for daily living. Poorer Myanmar and Cambodia, on the other hand, have not electrified all of their territory.

Myanmar, for its part, is considering establishing a conservation area around the mangroves near Myeik, whether that is a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, a geopark or a RAMSAR Wetland Conservation site.

“Then, the Myanmarese would also have to decide if and how they would protect their natural mangrove systems, which are very vast,” Böer said.

He added: “It would be in the best interest of nature conservation, but also nature conservation for the people who are living there. We don’t want to damage the people who are living on charcoal production.”

If anything, mangroves are set to become even more ecologically important than they already are as the climate continues to change worldwide. In addition to the benefits they provide when it comes to fishing, storm protection and carbon sequestration, mangroves may actually expand amid rising sea levels.

“We have an abundance of seawater in the world, and mangroves are halophytes, or salt plants,” Böer said. “Depending on the species, they can grow in full-strength seawater, they can grow and reproduce and germinate, so in times of sea level rise, it might be very important for the future of conducting coastal forestry to have mangroves available because they can grow new trees — they can grow up to 60 meters [197 feet] in height and they have very good wood which be used as a cash crop.”

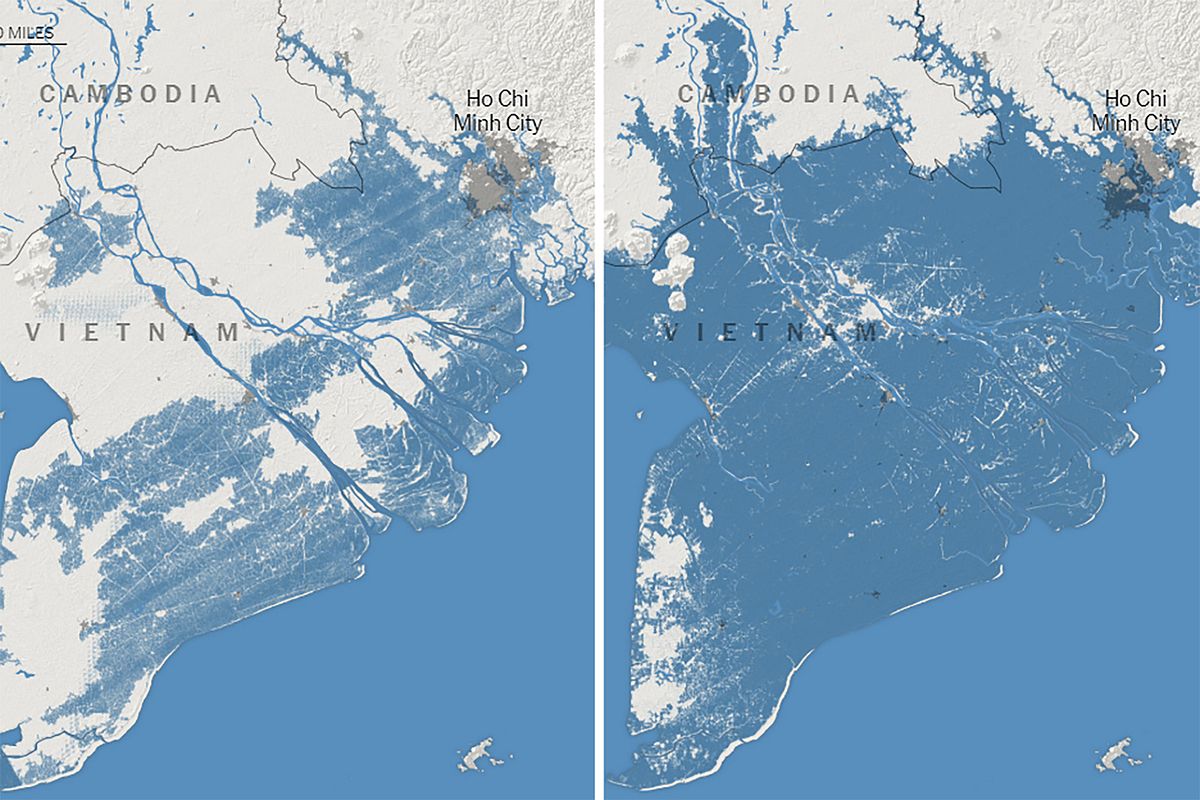

Such a scenario could come into play in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam’s most fertile rice- and fruit-growing region, parts of which are already feeling the impact of salinization as the sea inches upstream. Mangroves can survive such conditions while also serving as an incubator for shrimp and fish farms which can be destructive when not managed properly – which are key to the region’s aquaculture industry.

“If the sea levels rise as predicted, then the rice will be exposed to salinization, and rice is not very salt-tolerant,” Böer said. “So it would be possible for them [farmers] to grow mangroves, though they cannot be eaten, so that is another problem.”

Across the Greater Mekong, rapid economic growth has dramatically altered natural ecosystems, with forests, including mangroves, often bearing the brunt of industrialization and urbanization.

This article is republished from Mongabay under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.