“The best way to overcome fear is to face it,” 33-year-old Hương Nguyễn thought when she decided to volunteer as a frontline worker during Saigon’s most deadly weeks of the pandemic.

Hương was one of thousands of young volunteers from the Go Volunteer! network, an NGO undertaking pandemic-related initiatives in Saigon. Having known about the organization since the end of May, she had debated the decision to join many times before finally taking the plunge in July. That was when the entire city became a red zone, with 4,000–5,000 new COVID-19 cases every day.

“I’ve participated in many charitable campaigns since I was in university, so when Saigon and Binh Thanh District where I live recorded record-breaking case loads, I was very concerned and wanted to help,” she explains. Still, it wasn’t a choice made lightly. Her company, where she works as a study abroad consultant, allowed employees to work from home. But after joining the frontline, she found that she had to spend her limited breaks and evenings off from pandemic work to complete tasks for her actual job.

“There were a few days when people came in droves to get vaccinated and my team, which does data input, had to stay until 9pm. I brought my laptop with me to work in my spare time,” Hương says. “I deliberated joining for a month. But that’s just my nature: I walk the walk, even though I was very conscious of the immeasurable risks of this volunteer trip.”

Once-in-a-lifetime experiences

I got to know Hương via a mutual friend. Browsing through the photos she posted on her social media feed, I couldn’t make out which role she was playing in the pandemic-fighting efforts: sometimes she was at the stadium where people were getting their shots, at other times she was wedged amid tiny alleys with COVID-19 test kits. She shares that she had never cycled through as many “job positions” as she did during those two months volunteering, from vaccine data entry to crowd control to rapid test squads.

To start, Hương was deployed to vaccination points in Binh Thanh District to enter personal information of local residents into the central database, and to get people to queue in an orderly manner. “Our data entry team worked on computers all the time and the task required a lot of precision, so we had an entire room to ourselves. I was quite surprised at first because the job description sounded a little...leisurely,” she reminisces. After just a day, she realized that no step in the process was easy. “Some days we received nearly 3,000 people and couldn’t finish keying their info until unearthly hours.”

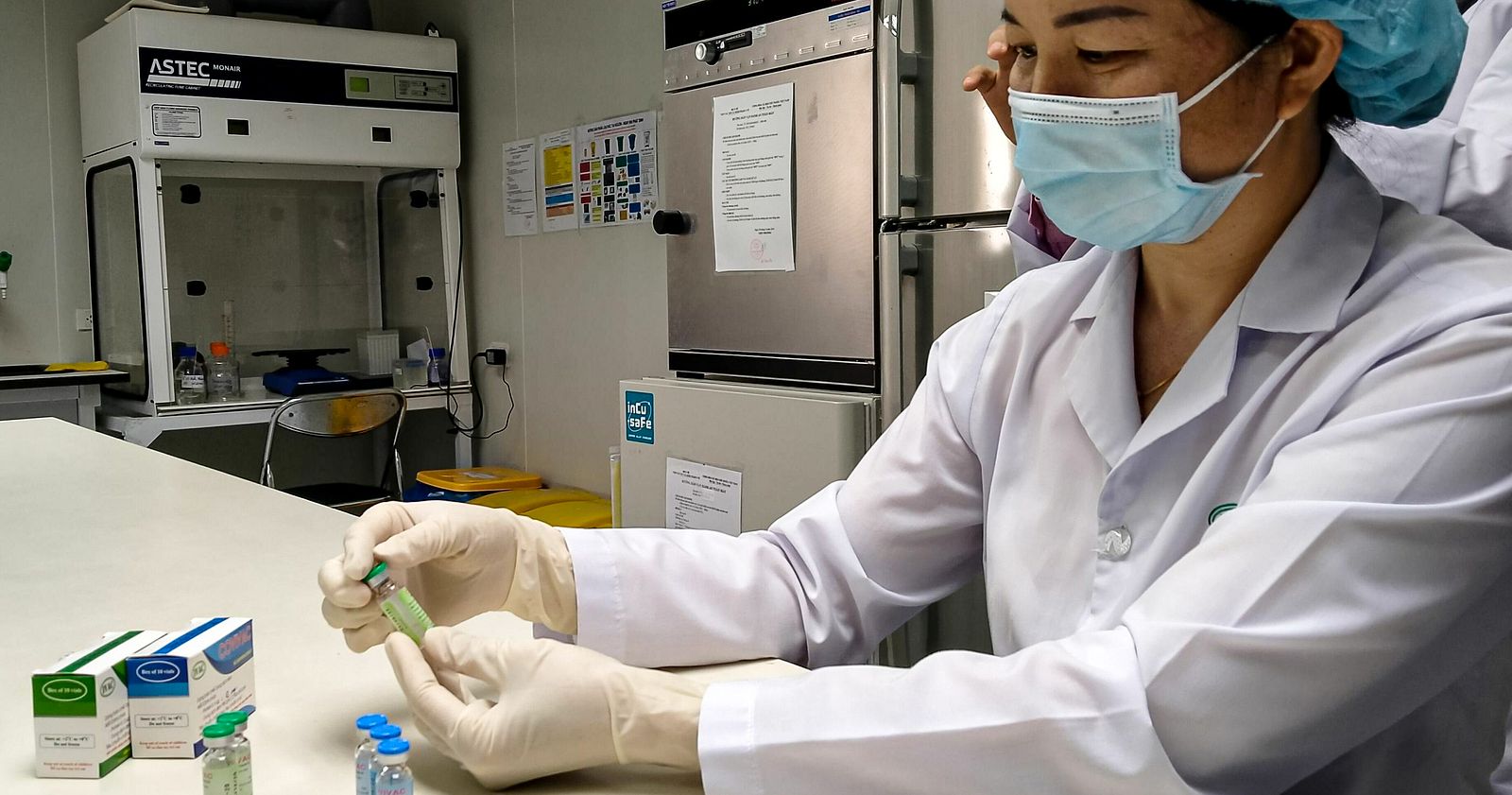

After a stint on the data input team, Hương admitted feeling hesitant before starting to work at vaccination points and in teams conducting at-home fast tests for residents: “Part of it was because [it involved] direct contact with households in the red zone, the other part was because I’ve never assisted on healthcare tasks before.” After 10 minutes of training, she joined a five-person testing squad, officially on her third position in a month on the job.

“The toughest part wasn’t being in contact with many people, but those protective suits,” she shares. Donning an air-tight “hazmat suit,” complete with gloves, socks and a visor, for nine hours a day is no easy feat even on the cooler rainy season days of Saigon. “Everybody is wet from top to toe after taking it off; even our inner clothes are soaked.”

“Because of the many layers, people outside can’t hear us well most of the time. There were days when I fainted because I had to talk a lot and talk loudly in shifting weather conditions. My teammates freaked out.”

“I will continue volunteering until Saigon recovers.”

When I made the appointment to interview Hương for this article, I suggested a later time in the evening, thinking that it might give her time to have dinner or rest. She replied that she could squeeze us in at 6:30pm after she was done for the day. In our one-hour phone call, she passionately relayed her story with an energy that even people who’ve been working from home for the past four months like me would find surprising.

According to Hương, volunteering has changed her mental state for the better: “Being able to move around, meeting many new people, including so many young people in their 20s with an inspiring source of positivity, has calmed my nerves a lot. I worried less compared to the period spent sheltering alone at home.”

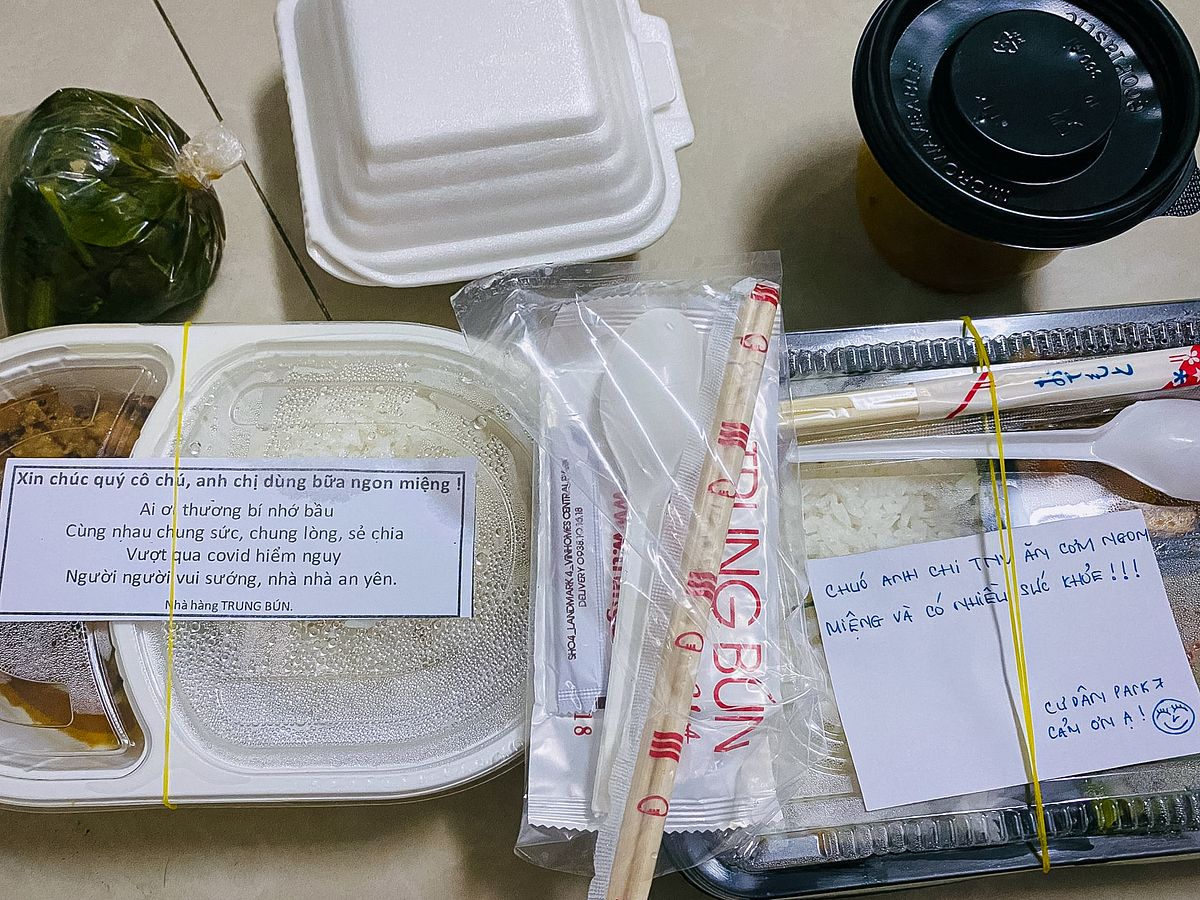

During our interview, apart from the complaint about the stuffiness of the protective gear, Hương mentioned many other endearing details of her time on the frontline. For example, there were the bananas or snacks that residents from a hẻm gave the team; a story about a ward official with a talent for catching fish with his bare hands; or the one time she accidentally called a policeman “uncle” and upset him, etc. When asked what she feels grateful for, she responded without hesitation: “Smiles, friendship, and medical knowledge to protect myself. We had health checks and rapid antigen tests every two or three days. Even though we met many people, we followed pandemic guidelines, so it wasn’t much of a worry.”

Hương also expressed a sense of awe and respect for the intensity with which medical practitioners carried out their job: “There were moments when we were completely spent, but looking at the selflessness of the doctors, it was clear that what we did couldn’t compare. I talked to a physician at the vaccination point. He said that after ending his tasks there in the late afternoon, he would return to his hospital to treat his own patients. On days with many admissions, he usually works until 2am, sleeps at the hospital, and then wakes up at 6am to prepare to travel to the vaccination site.”

When the outbreak eventually thing of the past, people will probably create documentaries and write books about these historic moments of our collective memory. In my mind, I picture black-and-white footage showing the bright and dynamic portraits of our frontline workers. Hương and 60,000 other volunteers in their instantly recognizable blue suits will no doubt be part of them.