If you help save hundreds of thousands of lives via medical breakthroughs and establish one of the country’s first and most advanced research institutes, but also assist in the colonial regime’s brutal oppression of natives via a draconian alcohol monopoly, do you get a street named in your honor? If you’re Albert Calmette, you do.

In 1863, Calmette was born “to the booming of cannon saluting the seizure of Mexico City”: a sign that his native France’s imperial ambitions, at their height then, would factor heavily in his life and achievements. The third son of a high-ranking civil servant, he aspired to a life of armed adventure from a young age: polished bayonets and bugle ballads, cavalcades and sexy pith helmets, nights hunched beside oily lamplight in distant outposts carving up remote swatches of jungle known only from map lines, wine-weary and as leery of venereal disease as uprisings. Alas, a childhood bout of typhoid dashed his military ambitions and Calmette turned his talents to medicine.

After graduating from the naval military school, a desire to see the world led Calmette to take a position as a doctor on a warship. He saw action in the battle of Fuzhou in China, which was part of the Sino-French War which popped off because Chinese troops allegedly ambushed a French unit in Bac Le in northern Vietnam. While in the area, Calmette had an opportunity to visit Saigon, declaring it “the most agreeable town I’ve seen in the Far East,” though “I shall perhaps never return.”

The Sino-French War. Photo via Gharbieyeho.

Calmette would undoubtedly return but he had a few adventures to embark on first. After gauzing up wounded soldiers in China, he worked on a floating hospital in Ghana. There he gained intimate knowledge of tropical maladies, yet late-century malaise pulled him away after only a couple of years. Following a brief respite in France to get married, he took a job at a hospital in Canada — another place France had its greedy, brie-sticky fingers wrapped around.

No one wants to eat cod marred with garish red spots, understandably. So when the fishing port’s stocks were stricken with the condition, colonial authorities prioritized finding a cure. Calmette discovered a spore in crude curing salt brought on the condition and quickly remedied the issue, restoring profits.

The intelligence and ingenuity Calmette showed in solving the red splotch scourge earned him a spot at the new and esteemed Pasteur Institute in France. He further set himself apart there and was offered the role of establishing a satellite institute in the recently formed Indochina colony. At age 28, he arrived in Saigon, tasked with combating the many medical emergencies ravaging the area.

Calmette traveled to Vietnam on a boat filled with rabid rabbits. Dedicated to continuing his mentor Louis Pasteur’s work in eradicating the disease, he constantly had to infect new animals to keep strains alive long enough to have a live sample with which to create a vaccine in the colony. While some officials in Saigon denied it even existed and others claimed Calmette was the one to introduce it to the area, according to “Imperial Intoxication” by Gerard Sasgas, he was able to successfully protect many civilians from rabies with the vaccine.

He also focused on other diseases, including dysentery and cholera. One of his major accomplishes was in combating smallpox, which was responsible for 90% of infant deaths and the blinding of many more in the colony. Using local water buffaloes, he developed an inoculation method that allowed more 500,000 people to be vaccinated in just two years.

Calmette with the first two people in Asia to receive post-exposure prophylaxis. Photo via ResearchGate.

Sadly, the colonial regime had piastres — Indochina's official currency — on the brain and pressured him to research opium and alcohol: lucrative industries that they hoped to control. From a wooden shack annex, Calmette busied himself trying to improve the process of drying opium and producing alcohol. Much to the detriment of Vietnamese, he was quite successful. His discovery of a certain yeast, delightfully named Amylomyces rouxii (seriously just let it drizzle off your tongue), reduced the fermentation time of opium from one year to 30 days. Now fiends could get their lips around the mesmeric smoke with far lower storage and preparation costs. Yay!

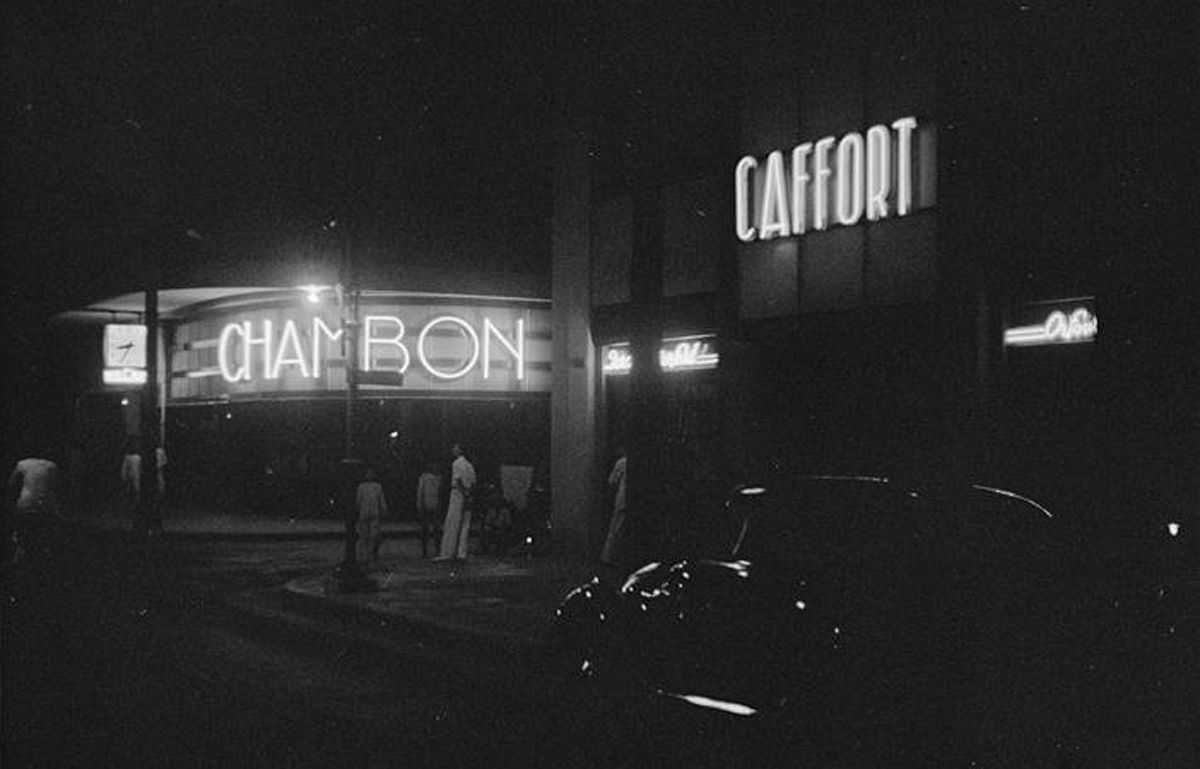

He made similar strides with alcohol. Following European advances in the science of wine and beer fermentation, he isolated the microbe responsible for making native Vietnamese rượu, known in English by its misnomer, rice wine. Now massive factories could churn out industrial hooch at staggering rates. Of course, the locals neither liked it nor were they willing to let it replace their culturally valuable home versions. Instead, the liquor and its accompanying customs agents fomented great dissent, prompting backlash and bloodshed while radicalizing an entire populace against the avaristic invaders.

It would be comforting to view Calmette as akin to Peter Laurids Jensen — the man who invented the world’s first loudspeaker to play music to large groups of people who was justifiably horror-stricken to witness Hitler and other dictators co-opt it to spew hate and inspire genocide. Unfortunately, Calmette contributed more to the problem than simply streamlining liquor production. Following Pasteur's belief that science must intermingle with commerce, he helped to draw up plans for a monopoly and the specifics of the laboratory needed to maximize production. He even went so far as to exaggerate the potential success of his plans, causing further damage for all involved. Lifelong friends with the entrepreneurs who got rich from the operation, for his work Calmette was paid an additional 250,000 francs, equivalent to nearly one million euros in today’s economy.

Calmette also worked extensively to find an antidote to snake venom. Long before Saigon was overrun with bubble tea shops and backpackers wearing elephant pants, cobras slithered in shadows and shipping boxes, winding coils around nightstands and nursery cribs. And while he wouldn’t perfect his anti-serum before leaving the country, it’s a good thing he eventually did, because in 1894 he was bitten by a poisonous snake and was able to save his own life. Not only did he learn that small doses of venom can serve as anti-venom, which were distributed throughout Indochina, he introduced toxin-therapy and helped evolve the understanding of using poisonous substances in moderation to remedy ailments.

Calmette depicted working against snake bites and other illnesses. Photo via Wikipedia.

While Calmette successfully laid the foundation for a fledgling hospital, he never fell in love with the country; never taking to rice wine nor the towering dipterocarp trees whose verdant canopies once soothed the city the way a lullaby soothes a child's gassy belly. Unlike his peer Alexandre Yersin, who resided in Vietnam for his entire life, after two years and weak with typhoid, Calmette blew this bamboo stand and scampered back to France. After being appointed a Knight of the Legion of Honor, he was given the opportunity to develop a Pasteur Institute in Lille. He stayed there for 20 years and made the most significant discovery of his career.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, George Orwell, Emily Bronte and Frederic Chopin — a lot of famous people throughout history have died from tuberculosis. The bacteria-borne illness that fills lungs with blood and sputum while sending sufferers into a series of night sweats and chest pains has been one of the leading causes of death throughout the world ever since early humans abandoned their nomadic lifestyles and started getting too cozy with their livestock. But with fellow-scientist Camille Guérin, Calmette was able to create a vaccine that could guard against it. It's because of these two men that you don't have the disease, as their vaccine is still the de facto one given to children all over the world.

Despite this great breakthrough which undoubtedly saved the lives of millions, Calmette’s life ended in tragedy. A few years after he invented the vaccine, dubbed Bacillum Calmette-Guérin or BCG in honor of its inventors, a virulent strain was accidentally given to 251 children. It killed a quarter of them and made many others ill and blind. The incident filled Calmette with great guilt and plummeted him into a despair that never lifted before he died at the age at 70.

Calmette's legacy lives on in Vietnam through the Pasteur Institute, which still actively researches illnesses such as dengue, cholera and HIV/AIDS. I suggest pouring one out in honor of all his contributions to modern medicine, just make it local rice wine and not the horrendous Hanoi Vodka he helped pave the way for.

Bust inside Saigon's Pasteur Institute. Photo via prompting backlash and bloodshed.