Though now little more than a rat-infested sewer, the former canal Bonard was once a busy waterway which made an immense contribution to the economic prosperity of Chợ Lớn. As work begins to restore this sole surviving inner-city canal to its former glory, Tim Doling looks at its history.

Related Articles:

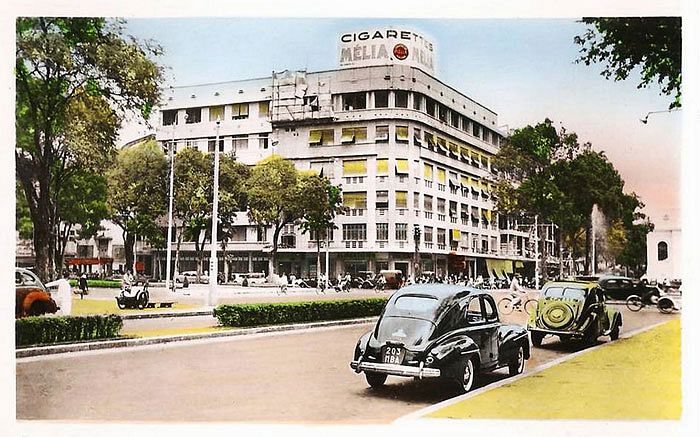

- Icons Of Old Saigon: The Electricity Building

- Icons Of Old Saigon: Établissements Bainier Auto Hall

- Icons Of Old Saigon: The Hotel de L’univers

A map of Chợ Lớn dated 1874 suggests that the easternmost section of the canal Bonard was dug at an early date as a branch of the Quới Đước creek, perhaps by the French Navy as part of a network of military waterways in the west of the city.

The easternmost section of the canal Bonard existed before 1874.

However, by the 1880s, with water traffic on the increase and the upper reaches of the Lò Gốm creek becoming silted up, the authorities realised the need to extend the canal westward.

In November 1888, 17 hectares of land was granted to the Chợ Lớn Municipal Council to turn the existing waterway into a 1.5km canal connecting the Quới Đước and southern Lò Gốm creeks. This was followed in June 1889 by an Ordinance instructing the Council to commence work on the canal, the quays alongside it and the roads leading up to them. The project also included the construction of a 55,000m³ boat-building basin (the bassin de Lanessan) containing “dry docks for the repair and construction of junks.”

However due to finance and land clearance issues, the project suffered significant delays and the canal was not completed until 1893.

The completed canal Bonard and the bassin de Lanessan boat repair and construction yard are depicted on this 1893 map of western Chợ Lớn.

Although the name canal Bonard was chosen at the outset of the project, it was decided in 1893 to change the name to canal Fourès, in honour of Lieutenant Governor Augustin Julien Fourès (21 May 1889–9 Aug 1889, 11 Sep 1892–25 Mar 1894), who championed the project and pushed it through to fruition. However, it seems that his contribution was quickly forgotten, since by 1907 the canal had reverted to its original name, canal Bonard. To add to the confusion, it also seems to have been known throughout the colonial period by the alternative name “canal de la Distillerie,” in reference to the Distillerie de Cholon, a large rice alcohol factory which opened next to the waterway in 1892.

The "canal Fourès" - the name by which the canal Bonard was known until the early 20th century.

By the early 20th century, five large road bridges had been constructed over the canal Bonard, carrying the rue de Minh-Phung (modern Minh Phụng), the rue Danel (after 1928 a joint rail-tramway bridge, now Phạm Đình Hổ), the rue de Palikao (modern Ngô Nhân Tịnh) and the rue de Go-Cong (now Gò Công) respectively.

The Canal Bonard viewed from the Gò Công Bridge in the 1930s.

However, perhaps the canal’s best-known bridge was the one which spanned its easternmost end at the “T junction” with the Quới Đước creek. This was the famous Pont des trois arches (Three-arch bridge), a pedestrian structure built in the 1920s by the Société d'exploitation des établissements Brossard et Mopin, and reportedly funded by nationalist journalist Nguyễn Văn Sâm and his wife, the younger sister of Chợ Lớn businessman Trương Văn Bền. In 1958, this unusual bridge was used as the backdrop for the murder scene in Joseph L Mankiewicz’s 1958 film version of Graham Greene’s The Quiet American. It survived until the late 1990s.

The Pont des trois arches (Three-arch bridge), which spanned the junction of the canal Bonard with the the Quới Đước creek.

It was during the 1920s that the canal Bonard really came into its own. By that time, the old Chợ Lớn Central Market (located on the site of today’s Chợ Lớn Post Office) had become too small to cope with the number of traders. The filling of Chợ Lớn’s inner-city waterways in 1923-1926 hastened its demise by making it impossible for ship-owning merchants to access the market by boat.

Significantly, the canal Bonard and the lower section of the Quới Đước creek which connected it to the Bến Nghé creek were the only inner-city waterways to be excluded from the government’s 1923 waterway-filling scheme. Recognising how crucial it was to guarantee the merchants waterway access to the city market, wealthy businessman and philanthropist Quách Đàm (Guō Yǎn, 郭琰, 1863-1927) offered to pay for the construction of a brand new market on the north bank of the canal Bonard, where he owned large tracts of land. The site he chose was the bassin de Lanessan, which had to be filled before construction began in 1926. The new Bình Tây Market opened to the public in September 1928.

The canal Bonard viewed from the Palikao Bridge in the late colonial period with the Bình Tây market in the background.

Known after 1955 as the Hàng Bàng (or Bãi Sậy) canal, the old canal Bonard remained one of the city’s busiest waterways until the mid 1960s, when war began to impact negatively on agricultural production in the Mekong Delta. By the end of that decade, the canal had fallen into disuse and temporary housing had been built along its banks, turning it into an open sewer.

“Saigon slums 1963” (unknown photographer).

In 2000, the western section of the canal from the Lò Gốm creek to Ngô Nhân Tịnh street was filled and houses were built over it. Today, all that remains is the severely-polluted eastern section, connected to the Bến Nghé creek by the Quới Đước creek.

The Hàng Bàng canal (formerly the canal Bonard) today.

In 2015, work began on a US$100 million project to reinstate this historic canal in its entirety, with the aims of reducing environmental pollution, improving public health and reducing chronic flooding. Temporary housing will be relocated and the quaysides – which still contain a number of important heritage buildings – will be landscaped for both visitors and residents to enjoy.

Tim Doling is the author of the walking tours book Exploring Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2014) and also conducts 4-hour Heritage Tours of Historic Saigon and Cholon. For more information about Saigon history and Tim's tours visit his website, www.historicvietnam.com.