Built by the French at the mid-point of historic rue Catinat, the Municipal Theatre is one of Saigon's most iconic landmarks.

Related Articles:

- Old Saigon Building Of The Week: 93-95 Đồng Khởi

- Old Saigon Building Of The Week: 128 Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai

- Old Saigon Building Of The Week: The Grand Hotel

Western theatre was popular in Saigon from the earliest years of the French colony. For more than a decade after the arrival of the first European settlers, performances by visiting French troupes were held regularly in the Salle de spectacles of the first Governor’s Palace, a series of wooden buildings which had been purchased in kit form from Singapore and assembled in 1861-1862 for Admiral-Governor Bonard.

The first purpose-built city theatre was constructed in 1872 on the site of today’s Caravelle Hotel. According to an article of 3 June 1880 in the Courrier de l’Indochine, this first Saigon theatre specialised not in the operas of Gluck or Mozart, but rather in “the works of Offenbach, Lecocq and other geniuses of the comic genre.”

From 1862-1872, performances by visiting French theatre troupes were held regularly in the Salle de spectacles of the first Governor’s Palace.

Unfortunately, the first Saigon theatre was built from wood, and in 1881 it was destroyed by fire. However, it was rebuilt in the following year, using more durable materials. Describing this second theatre in 1887, Le Figaro newspaper commented: “it is simple and the architecture is very primitive – but it is impossible to burn down!”

Writing in August 1893, La Revue hebdomadaire was more flattering. “It’s so pretty, our Saïgon theatre, with its boxes decorated with hanging plants and its wide verandahs filled with flowers! What more wonderful setting could there be in which to meet pretty ladies wearing the latest fashions, officers in uniforms embroidered in gold, elegant gentlemen, and mandarins dressed in rich silk costumes?” Two decades later, George Dürrwell would write nostalgically about the former theatre, which he described as “so small and so simply decorated, yet so cosy and intimate, surrounded by lawns and shaded by large trees.”

The second Théâtre de Saïgon (Association des Amis du Vieux Huế).

The location of the second Théâtre de Saïgon on the site of today's Caravelle Hotel is indicated clearly on this 1893 map.

As early as 1893, the powers-that-be decided that Saigon needed a larger and more impressive theatre building, one which better reflected the perceived glories of the French empire.

In 1895, a design competition was organised and the submissions of three architects – Ferret, Genet and Berger – were shortlisted. Eventually, the judges selected the design of Eugène Ferret, who reportedly had taken his inspiration from the Petit Palais in Paris. Early in the following year, Ferret’s winning plans for the new 800-seat “Grand-Théâtre de Saigon” were placed on display at the 1896 Exposition du théâtre et de la musique in Paris.

Work began in late 1896, and Saigon’s third and current theatre was completed in late 1899. It was inaugurated on 15 January 1900, in the presence of Saigon mayor Paul Blanchy and Prince Waldemar of Denmark, who was then making a state visit to Indochina. The inaugural performance featured the Asian premiere of Jules Massenet’s opera La Navarraise.

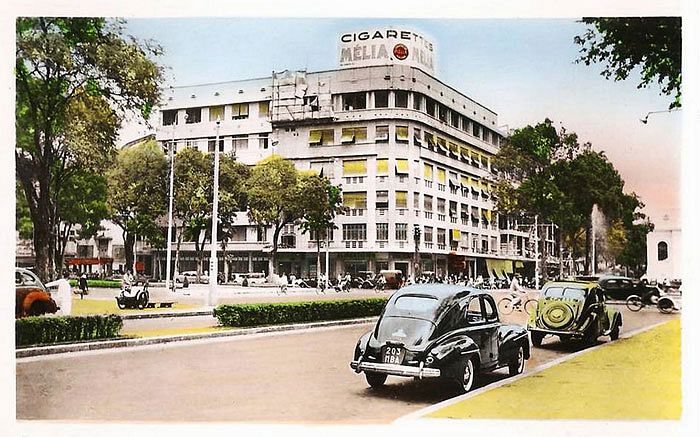

Théâtre de Saïgon in the early 20th century.

Ferret’s design was widely praised. The arts correspondent for Le Monde (13 January 1901) described the theatre as “an architectural marvel,” while L’Indo-Chine 1906, by Joseph Ferrière, Georges Garros, Alfred Meynard and Alfred Raquez, commented: “The monument is very fine, indeed, almost luxurious, and cleverly laid out for the needs of the theatrical arts in quite irreconcilable climatic conditions.”

However, at the outset, the theatre’s substantial construction cost – over 2.5 million francs – attracted much criticism, both in the colony and in France, from those who believed that the money would have been better spent on building a replacement Central Market, or upgrading the city’s inadequate utilities.

Securing enough annual funding to run the new venue proved to be an even bigger headache.

As early as the 1870s, the city decided to engage the services of a director-impresario to run the Saigon theatre and to ship out performing companies from France to perform in it. Before the inauguration of the Grand-Théâtre de Saigon, the colonial records afford us only occasional glimpses of the work of these early director-impresarios, larger-than-life characters such as Emile Pontet and Louis Achard, who constantly fought their corner at municipal council meetings in order to secure an adequate annual subvention.

In advance of the opening of the new “Grand Théâtre Municipal de Saigon,” the authorities announced with great fanfare the appointment of Messrs Boyer, Baroche and Compile as director-impresarios to run the new venue. The decision to overlook the incumbent theatre director Paul Maurel was a controversial one, and must have been very hurtful for Maurel himself, particularly since senior partner Aristide Boyer had worked under him for several years as the previous theatre’s secretary general.

After considerable debate, the new theatre was awarded a 200,000 franc annual operating subsidy, out of which 120,000 francs was to be paid by monthly allowance of 20,000 francs to director-impresarios Boyer, Baroche and Compile, and 70,000 francs was allocated for company travel. Just 10,000 francs was provided annually for renewal or maintenance of theatre equipment. It should be remembered that initially, because of the heat, the theatre only functioned for four months of the year (October-January). By 1910, Saigon’s “theatre season” had been extended by two months until April.

However, within just five months of the opening of the new theatre, Boyer, Baroche and Compile had “accumulated a considerable amount of debts” and resigned their position. Thereafter, the municipal authorities decided to engage their director-impresarios on an annual basis – but not before contrite council members had invited Paul Maurel back to clean up the financial mess left by his predecessors.

The Théâtre de Saigon continued to receive a large annual subsidy for the presentation of “opera, comic opera, operetta and comedy by visiting French theatre companies” until the late 1920s. Then, against a background of economic downturn and increased competition from other places of entertainment, the municipal government pulled the plug. During the later colonial period it was almost exclusively rented out for amateur events and the occasional gala performances.

During the Japanese occupation of Indochina (1940-1945), the French Vichy authorities moved to eliminate visible symbols of the now moribund Third Republic. and the façade of the theatre was completely remodelled. Then in 1944, it was seriously damaged by Allied bombing.

An aerial photograph of the Théâtre de Saïgon in the 1940s.

The Théâtre de Saïgon in the late 1940s after the façade was modified.

Following basic repairs in the early 1950s, the theatre was used in the wake of the Geneva Agreement of 1954 as temporary accommodation for homeless migrants from the north.

After 1955, the theatre building was completely refurbished and transformed into a National Assembly building. When the constitution of the Republic of Việt Nam was revised in 1967, creating a bicameral parliament, it became the Lower House (Hạ Nghị viện) of the National Assembly, while the Diên Hồng Hall (the former Chambre de commerce) became the Upper House (Thượng Nghị viện) or Senate.

The Municipal Theatre in July 1972, functioning as the Lower House of the National Assembly, photo by Kemper.

Reopened as a theatre in 1982, it was completely refurbished in 1995-1998 with French assistance to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the city of Saigon. As part of this project, the Municipal Theatre was provided with state-of-the-art electrical equipment, air-conditioning, lighting and sound systems and fire and safety equipment. Many of its original architectural and decorative features were also reinstated at this time, including the stone veranda and white stone statues at the entrance, granite tiled floors, chandeliers, bronze statues in front of the lobby stairs and auditorium arch and wall bas-reliefs.

The Municipal Theatre today.

Tim Doling is the author of the walking tours book Exploring Hồ Chí Minh City (Nhà Xuất Bản Thế Giới, Hà Nội, 2014) and also conducts 4-hour Heritage Tours of Historic Saigon and Cholon. For more information about Saigon history and Tim's tours visit his website, www.historicvietnam.com.