If you were a book publisher and saw a sudden spike in sales for a book published years ago, how would you explain it?

If an influencer or famous person, such as a singer or actor, mentions a work in an interview, it may create enough interest amongst their fanbase to drive purchases. This is exactly what occasionally happens for presses here in Vietnam, including for translated works. If they witness a surge in popularity for one of their Korean translations, for example, it's likely that Vietnamese K-pop fans heard a favorite singer mention it an interview.

유령의 시간 (Ghost Time / Thời gian của ma).

Because I do not speak Korean, my familiarity with Korean literature is very limited, which made me curious what the climate is like for Vietnamese readers. Last year I enjoyed a chance meeting in Saigon with the lovely Korean writer, Kim Yi-jeong, during which she described the positive experience of having her novel, 유령의 시간 (Ghost Time / Thời gian của ma), translated into Vietnamese. To learn more, I got in touch with her publisher, Nhã Nam. They connected me with Vương Thúy Quỳnh Anh, an in-house editor and translator at the time, who was able to give a behind-the-scenes look into the path a book takes from Korean into Vietnamese.

“There are not a lot of [Vietnamese] people that read Korean books because of their origin; they look at the content and the title and they decide to buy it… not because they want to know more about Korean culture,” Quỳnh Anh explained, countering my assumption that Vietnamese interest in Korean music, fashion and film would result in novels from South Korea becoming popular. It turns out, people pick up Korean translations simply because the story sounds appealing.

While Korea may be the setting of many Korean novels published in Vietnamese, it’s not the most appealing aspect for Vietnamese readers. Quỳnh Anh said that the readers are drawn to “best-seller books that focus on the journey of the main character [...] they find something difficult in their life so they go back to their past, or travel to a new place or do something different to find a new way to accept their current life.” These familiar plot arcs focus on the universal elements of the human condition and the idea that each journey has its own appeal and merits. She has also observed that in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, readers gravitate towards calming, stress-reducing narratives with happy endings.

Vương Thúy Quỳnh Anh is currently a freelance Korean-language translator.

If Vietnamese readers aren’t overly concerned with the books including Korea-unique elements, neither are they on the lookout for mentions of Vietnam. Quỳnh Anh said that she has not encountered much mention of her home nation in the novels she has worked on. Vietnam does, however, appear at times amongst the thousands of books released in Korea each year. South Korea’s involvement in the Second Indochina War, particularly, has resulted in an older generation of writers exploring their experiences in or impacted by Vietnam. Kim Yi-jeong’s novel, for example, examines the wartime experience of her father. Comparing Vietnamese and Korean literature focused on conflicts of the second half of the 20th century would no doubt reveal intriguing parallels and contrasts while offering fascinating insights on each culture as well as the universalities of war, death and endured hardships.

The people behind the books

Literary translators come from a variety of backgrounds and end up in their positions for different reasons, but most share a personal interest in learning foreign languages. Quỳnh Anh said she first wanted to learn Korean to better follow her K-pop idols. A psychology major in university, she taught herself Korean via Facebook, a website called Talk to Me in Korean and song lyrics. As she became more fluent, she began to wonder if she could work as a translator. In 2018, Nhã Nam put out a call for translators. After earning a spot as a freelance translator for some time, Quỳnh Anh graduated to a full-time editor. She has since moved on and now works as a freelance translator.

While Quỳnh Anh and her peers can make a living as full-time literature translators and editors, money remains an issue within the industry. Corporate and business interpreting and translating will always pay better, to say nothing of working abroad in Korea. This makes finding skilled literary translators a challenge. Alas, this situation is not unique. A dearth of talented and passionate translators unconcerned with income is one of the largest barriers keeping more Vietnamese works from being brought to English readers, for example.

Some titles that Quỳnh Anh worked on.

Anytime someone can turn a hobby into a career, there is a risk that the original fun is lost. Indeed, Quỳnh Anh said that once she began spending five days a week, 8-to-5, in an office, tinkering with the Korean language, she engaged with Korean less in her free time. But she attributes some of her waning interest to her favorite K-pop idols growing older and transitioning to new career stages. It’s worth reflecting on the fact that a virtue of literature is that it falls victim to fewer fads than other art forms and generally does rely on the giddy energy of youthful discovery and identity construction. This means its appeal transcends and even unites age groups.

From Hangul to tiếng Việt: The translation process

Considering the thousands upon thousands of books released every year, I’m always fascinated by the selection process for the minuscule percentage chosen for translation. Whenever I stroll through bookstreet and stop beside a shelf to exclaim “How in the world is this in Vietnamese?” I was thus quite eager to learn how it works for Quỳnh Anh.

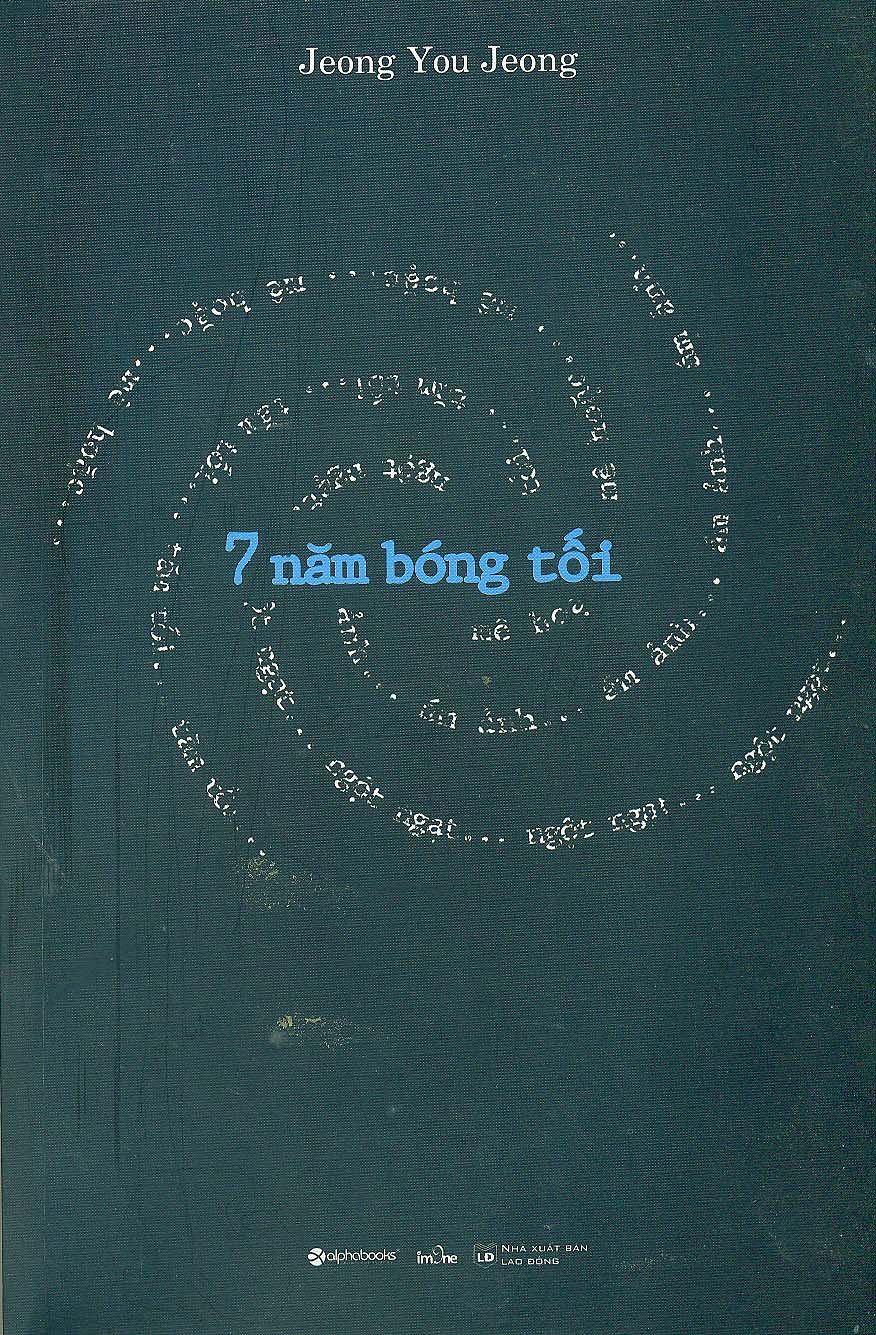

In 2015, Vietnamese translator Kim Ngân was among four winners at the Korean Literature Translation Awards for her translation of Jeong Yu-jeong's 7 năm bóng tối (Seven Years of Darkness).

Deciding what to translate is really not that complicated or mysterious. Quỳnh Anh said that editors and translators look for books based on what has won international or Korean awards, been widely translated into other languages; topped best-seller lists abroad; and any new releases from writers they admire or have been well-received in the past. After reading the description and some sample pages, they submit a formal pitch to their publisher’s leadership. If approved, a specific division works with the Korean publisher or author agent to acquire the translation rites. International literary events such as the Bejing Book Fair and the annual Seoul Book Fair help connect with authors, publishers, and agents while keeping attendees up to date with trends and developments in the Korean literary landscape.

Once a project has been assigned to an in-house or freelance translator, depending on schedules, it typically takes about three months for it to be ready for internal review and copy-editing. Occasionally graphic scenes, particularly those involving the human body and sexual activity, need to be trimmed. Then it goes to the in-house book design and marketing departments before it hits shelves at all the familiar Vietnamese retailers and online shops, accompanied by social media promotion.

In addition to passionate translators and editors, the viability of translations depends on institutional support, with various events, seminars, author visits and conferences supported by governments, foundations and publishers. Last year, for example, Saigon played host for the Meeting Vietnamese-Korean Literature at HCMC. Such opportunities help create excitement for translations and foster connections that ensure quality works are selected and whatever meager funds available can be allocated responsibly.

Poet Nguyễn Quang Thiều, Chairman of the Vietnam Writers' Association, presents a gift to Bang Jai-suk, Co-Chairman of the Vietnam-Korea Peace Literature Club during a seminar at the Vietnam Writers' Association. Photo via Công An Nhân Dân.

The Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTIK) has been particularly active in promoting Korean literature globally by supporting publishers and authors, and offering grants and training for translators. They also sponsor the annual Korean Literature Translation Awards, which selects winners from amongst a staggering number of languages. In 2015, Vietnamese translator Kim Ngân was among four winners for her translation of Jeong Yu-jeong's 7 năm bóng tối (Seven Years of Darkness) into Vietnamese for which she received US$10,000. In 2021, the book Tam Quốc Sử Ký - Tập 1 (Samguk Sagi - Chapter 1), written by Lee Kang-iae and translated by Nguyễn Ngọc Quế, was honored. In 2021, Vietnam's Women Publishing House coordinated with the LTIK to launch an online Korean literature book review. The organization recognizes and promotes 106 unique titles translated into Vietnamese since 2001.

Whether 106 books sounds like a great success or a travesty is a matter of perspective. It’s impossible to define what success for Korean literature in Vietnam would mean. It’s enough of a challenge to determine if any one book has exceeded expectations, as the only metrics available are sales numbers, scattered reviews online and the potential for prizes or grants awarded post-publication. The most important criteria for a reader rests within him or herself.