If you opened an American magazine, literary or otherwise, in the early 2000s and found any Vietnamese American byline, there’s a good chance it was Andrew Lam. The long-time journalist’s essays and short stories were amongst the first widely circulated in the US.

Since then, authors like Viet Thanh Nguyen, Ocean Vuong, Thi Bui, and Monique Truong have all found great success and contributed to the Vietnamese demographic’s prominence in the international publishing scene. During a recent lunch, Lam said that their ascension allows him a certain freedom; no longer do readers expect him to be speaking for the diaspora as a whole. Rather, now retired from his journalism day job, he can simply explore his art. This opportunity to indulge his creative impulses alongside his love for short fiction is evident throughout his latest collection, Stories from the Edge of the Sea. The book sees him shifting tones, subjects, and styles with an often sly wit and energetic desire to push the genre to its full potential.

Lam says that he never thinks about his audience when sitting down to write; he is first and foremost interested in entertaining himself. This focus on catering to his inner literature nerd collides with the common adage to write what you know. Thus, many of the stories focus on desire, generational and cultural expectations, and aging individuals within the Vietnamese diaspora reflecting on their lives, often at pivotal moments of change or realization.

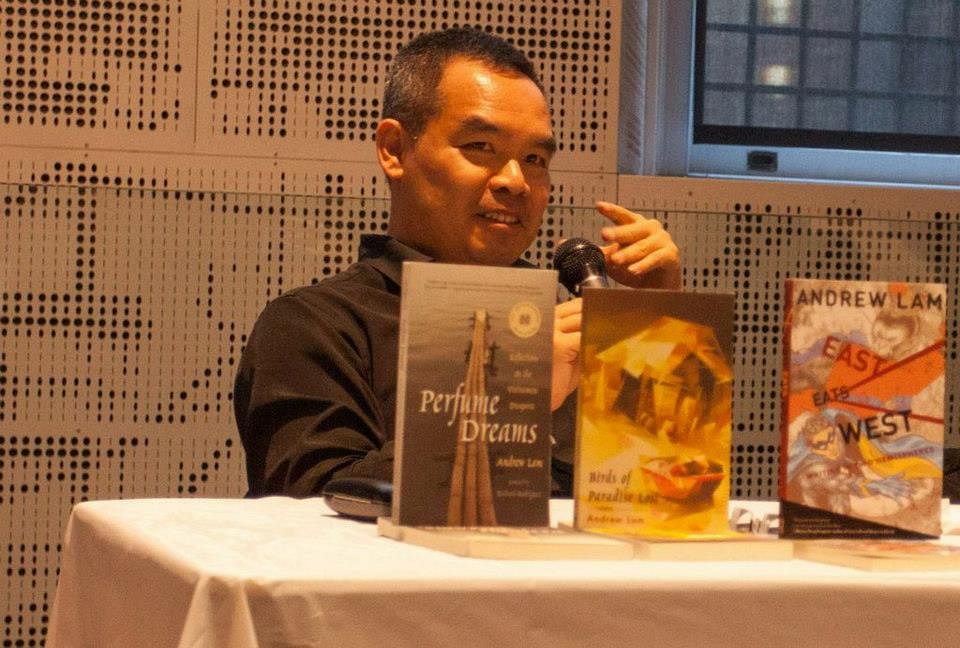

Andrew Lam at a reading with his first three books. Photo via Andrew Lam.

Romantic love in Lam’s stories is often wild, passionate, and doomed. Whether it's an instantaneous crush on a stranger who perpetually gets lost in the crowd at a Guggenheim art exhibition; a once-inseparable homosexual couple that reunites after one of the men has married a woman and had a child; or a couple that is separated by geography and circumstance — torrid emotional and physical yearning is unfulfilled or tragically impermanent. A certain sadness hangs over the book as numerous plotlines settle on an understanding that happiness is frequently brief or bittersweet. One should savor those moments, the stories suggest, because soon they will just be memories to look back on.

Stories from the Edge of the Sea is far from a depressing read, however. Lam offers welcome levity via several outright comedic pieces. Positioned as a pure, rapid-fire stand-up comedy routine with one-liners and riffs, ‘Swimming to the Mekong,’ is a companion to ‘Yacht People’ from his previous collection, Birds of Paradise Lost. At one point, for example, the comedian narrator quips: “So hey, here’s a cool idea for a new genre in porn: lazy porn! ‘Dallas does Lazy Susan.’ Why? Cuz Susan’s too lazy to do Dallas. It’ll be surreal. Lazy Susan’s so lazy she’s just gonna lie there and every cowboy spins and screws her while she eats her dim sum. Lazy Susan’s so lazy that after a giving few blow jobs, she’d be applying for unemployment benefits. Lazy Susan’s so lazy that she’d outsource all her hand jobs to India.” Encountering such crass passages juxtaposed with earnest stories of people pained by an inability to connect can be jarring at first, but ultimately underscores Lam’s artistic range and the multitude of voices the short story genre can contain.

Lam also understands that comedy is an effective way to speak truths. Thus, ‘Swimming in the Mekong,’ and the similar ‘Love in the Time of the Beer Bug’ contain caustic social critique and observations aimed at his own communities. “Now you would think that a country that defeated the French and then the US, would find western features fugly after seeing John Wayne shoot our people. But you’d be, like, WRONG,” the narrator says to the crowd. “Vietnamese put down those Amerasian kids right, cuz they say ‘these kids are all children of whores, fathered by American GIs.’ The kids were treated like dirt back in Nam. But don’t tell anybody, ok, it’s between us: Many of us want to look exactly like them. You know, light hair, blue or hazel eyes, straight nose, double eyelids, split chins, the works.” Such topics could be approached, possibly with less success and certainly less entertainment, via a conventionally restrained format, but where is the fun or creativity in that?

Photo via Andrew Lam.

Alongside these comedic outbursts and other inversions of familiar structures, such as ‘October Lament’ which tells the story of a deceased husband via archived social media posts and text messages, are tightly written and more straightforward works. A devotee of the short story genre, eager to discuss its merits, and how it's worth the challenges of brevity and limited readership, Lam is a master of placing fully unique and realized characters in moments of heightened consequences. ‘To Keep from Drowning’ is a standout example. In it, a single mother and her three teenage children walk to the ocean to celebrate a death anniversary. One child is secretly pregnant; one is embarking on a dangerous criminal life; and the third is developing a worrisome drug habit, all of which is being kept from the mother who is attempting to hide a terminal illness. The immensity of the family’s tragic past and fraught futures are revealed in the short distance from the metro station to the coast, with their uncertain futures drifting somewhere in the surf for the reader to discover. This story, as well as ‘The Isle is Full of Noises’ and ‘What We Talk about When We Can’t Talk about Love’ allow Lam to flex his full command of literary fiction. Not only are they powerful, engaging stories, but when he shows he can so expertly follow the so-called rules of fiction, readers will approach his less-conventional works with full trust and excitement.

After making his readers laugh, empathize, and reflect on the logic governing the human condition, Lam punches them in the heart. Stories from the Edge of the Sea ends with the devastating ‘Tree of Life,’ a eulogy for his mother. She was a 1954 migrant to the south who experienced severe sorrow and hardship during the wars, but he remembers her as a woman eager “To feed, to nurture, to protect. To react to harsh reality with kindness and generosity—this is the very essence of my mother.” Recounting small and large acts of personal and public kindness in Vietnam and America, he makes clear how she was the pillar of their family. Such a role would not be obvious to outsiders because Lam’s father was a famous general. But Lam writes: “I used to think of my father in a heroic light as a child. He who flew in helicopters and who called bombs to fall from the sky, and he who jumped down to earth in a parachute—he was like a thunder god, like James Bond, but my mother? Well, she was a true lioness. And when it comes to her family she was fearless.” Heroics, he suggests, has less to do with battlefield exploits and much more to an intrinsic generosity that means, even when Alzheimer's left her unable to remember where she lived or her own name, she couldn’t forget where the hungry, stray cats in the neighborhood lived so she could feed them. Without any of the sly asides or intricate plotting of the previous stories, the message of love and adoration he has for his mother blooms into a rumination on family, motherhood, and memory; it is a testament to kindness Lam passes on from his mother to the readers.