In 1927, after being abandoned for more than 60 years by its Spanish owners, the “Jardin d’Espagne” (today’s Lý Tự Trọng Park) seemed set to become the new home of the British Consulate General in Saigon…but it was not to be.

The participation of Spanish naval forces in the 1859 French conquest of Cochinchina is well documented. The event which had triggered the expedition was the execution on July 20, 1857 of the Spanish bishop of Tonkin, Monsignor José Sanjurjo Diaz. In response, the invasion fleet incorporated a large contingent of Spanish troops drawn largely from the Philippines.

In the aftermath of the conquest, several streets in Saigon were named in honor of Spain, including Rues Isabella, Isabella II and Palanca.

The Jardin d’Espagne on a 1923 map of Saigon.

The French authorities also granted the Spanish government a plot of land on which to build a consulate. According to the Colonial Council minutes dated November 8, 1928, the Conventions of May 15, 1864 signed by Spanish Acting Consul Manuel M Caballero, and of January 31, 1866 signed by his successor Fédérico Taque, ceded to the Spanish government “a 3,000m² plot of land on the north side of the junction between Rues Lagrandière and Mac-Mahon [now Lý Tự Trọng and Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa].” The concession of this land, now part of Lý Tự Trọng Park, was “made free of charge, but under the provision that the land is allocated solely for installation of a Spanish consulate and cannot be used for any other purpose”.

For a short while, an “old Annamite house” on the site was occupied by a group of Spanish naval officers. However, when the Spanish delegation eventually departed from Saigon, it had “failed to take effective possession of this land and abandoned the project of constructing a consulate in Saigon”. Thereafter, Spanish diplomatic affairs in Cochinchina were handled through the Consular Agent of Portugal.

Over the next half-century, as the surrounding streets were transformed into the so-called “Triangle of Power” (comprising the Law Courts, the Central Prison and the Palace of the Lieutenant Governor), this little piece of Spanish territory was christened the Jardin d’Espagne. During this period, it was looked after carefully by the staff of the Botanical and Zoological Gardens, who installed lawns and flowerbeds and took great care of its ancient banyan tree.

By 1919, the Consulate-General of Great Britain had outgrown its premises at 4 Rue Georges-Guynemer (present-day Hồ Tùng Mậu), and the search began for a suitable plot of land on which to build a larger diplomatic mission. The Jardin d’Espagne seemed to fit the bill perfectly, and later that year the British Consul-General wrote to the director of local administration asking if the French government “would be disposed to give its consent to the cession of this land from the Spanish government to the British government, which proposes to build a consulate there”.

The Jardin d’Espagne can be seen on the right of this early 20th-century postcard of the Lieutenant Governor’s Palace.

The three-way negotiations between France, Spain and Great Britain continued for another eight years. Finally, on November 10, 1927, “the Consular Agent of Portugal, M. Brodeur, in the name of the Spanish government, ceded and abandoned to the Consulate General of Great Britain represented by Mr. F Grosvenor Gorton, its rights to the Jardin d’Espagne”.

For its part, the Cochinchina government agreed that Great Britain would be substituted for Spain in the conditional rights to the land, which were once again linked exclusively to the construction of a consulate.

Had things proceeded as planned, the British Consulate in Ho Chi Minh City might now be in a very different location, and Saigon would have lost a valuable green space to redevelopment. But that wasn’t quite the end of the story.

After commissioning a long-overdue survey of the Jardin d’Espagne in December 1927, the British “encountered problems and communicated these to the Cochinchina authorities”. On January 21, 1928, Cochinchina Governor Paul Blanchard de la Brosse wrote to Grosvenor Gorton: “On the occasion of the transfer, you pointed out to me the inadequacy of the said land area with regard to its function, which is the construction of your consulate, and informed me that you would consider favorably the principle of exchange against another city lot administered through the Domaine locale.”

A subsequent report to the Colonial Council by Blanchard de la Brosse sheds further light on the problems encountered and also reveals the alternative lot which had been identified:

“The Consul General of Great Britain has noted that the area of this land is too small for construction of a [consulate] building, and secondly that the Jardin d’Espagne does not seem favorable for the installation of a consulate. For our part, the local administration believes that there is interest in maintaining the current function of the Jardin as a convenient square for walkers and children’s games in the very central area where it is located. Therefore, the principle of exchange of this land against Lot 7 of the subdivision plan of Boulevard Norodom is being considered. This latter terrain, situated between Boulevard Norodom (Lê Duẩn) and the Rues de Massiges (Mạc Đĩnh Chi) and Lucien Mossard (Nguyễn Du), has an area of 3,548m² and its market value is equal to that of the land known as the Jardin d’Espagne.”

A plan of the 3,548m² Lot 7 on Boulevard Norodom, which the British Consulate General was granted in exchange for the Jardin d’Espagne.

A formal offer was made, and on April 25, 1928, British Consul General F Grosvenor Gorton wrote to the governor accepting the substituted plot on Boulevard Norodom. This undoubtedly pleased the French; another report dated November 26, 1928 says of the Jardin d’Espagne that “its situation right in front of the Governor of Cochinchina’s Palace, from which it is separated only by the Rue Lagrandière, is not appropriate for the installation of a consulate”.

On October 6, 1928 Les Annales Coloniales carried an article entitled “The future British Consulate in Saigon”, reporting the exchange of the Jardin d’Espagne for the new plot on Boulevard Norodom, and explaining that “the plans, drawn up in London, will be executed in Saigon under the supervision of one or more architects who will come all the way from England. The design will be a reproduction of those buildings already constructed to serve the same purpose in Bangkok and some major cities in China; or rather, it will be a ‘Cochinchina adaptation’ of the commonly adopted type.”

A view of Saigon's Boulevard Norodom.

The replacement lot was formally ceded by the Domaine Locale on December 21, 1928, but the new British Consulate General at 21 Boulevard Norodom (now 25 Lê Duẩn) took several years to construct and was not inaugurated until 1934. Sadly, no photographs have survived of this building, which in the 1950s became the British Embassy to the State of Vietnam and then briefly to the Republic of Vietnam. It was demolished and rebuilt in its current form in 1958-1959.

The 1958-1959 British Embassy building, now the British Consulate General in Ho Chi Minh City.

Crucially, the land exchange of 1928 returned the Jardin d’Espagne to the Domaine Locale and it became a small municipal park.

After 1955 it was renamed Công Vien Liên Hiệp (Union Park) and, after 1975, Công Vien Lý Tự Trọng. Then in the early 1980s, the buildings which had stood on the adjacent plot of land were demolished and the park was doubled in size, so that today it stretches the entire length of the block between Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa and Pasteur Streets.

Abandoned by the Spanish and rejected by the British, the Jardin d’Espagne was eventually transformed into one of Saigon’s best-loved parks.

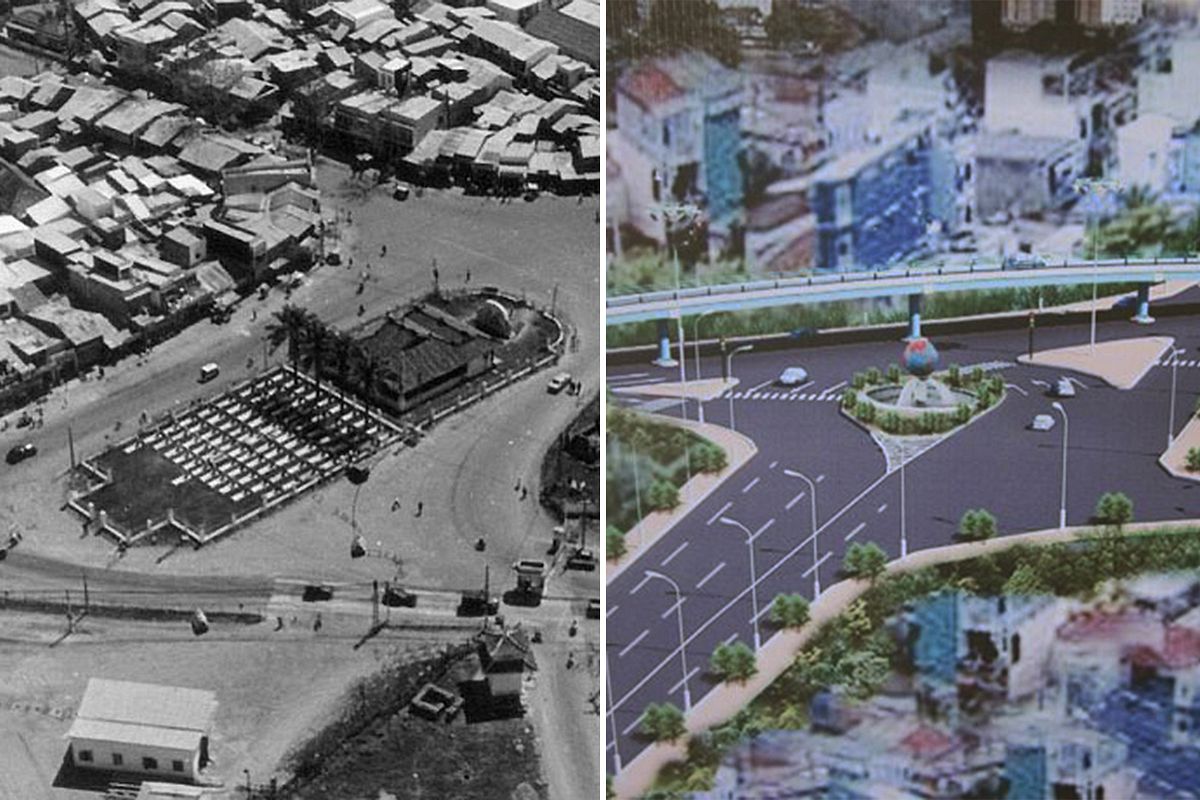

The former Jardin d’Espagne, now the Lý Tự Trọng Park.

In the early 1980s, the buildings which had stood on the adjacent plot of land were demolished and the park was doubled in size, so that today it stretches the entire length of the block between Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa and Pasteur Streets.