"A Việt Kiều customer living in France paid me a visit. She looked at my sofa and started tearing up because its design was so similar to one she had in her childhood home. She said she missed home and missed those days a lot,” Huỳnh Minh Hiệp, the owner of Lúa Cafe, says.

From outside, Lúa Cafe at 140B Nguyễn Văn Trỗi Street in Phú Nhuận District spots a similar setup to any other casual coffee place in Saigon. As one ventures deeper into its cozy corners, however, it’s likely to conjure up some memories thanks to the cafe’s expansive collection of 5,000 Saigon artifacts.

A tight connection to the land

I meet Hiệp during a weekend when he’s busy preparing for a trip to Bình Dương to hunt for new antiques. Of his start in antiquing, he points to a period in 1993 when a freshly graduated Hiệp took a job at Tân Sơn Nhất Airport’s duty-free shop.

A brief history of Vietnam’s currency, from Indochinese coins to the very first colored paper bills.

With many party tricks up his sleeve like drumming and magic feats, Hiệp often entertained tourists during airport visits and were given scores of foreign bills and coins of their countries. It got him to wonder if he should start seeking out more of these to make a collection of global currencies.

The idea was quickly actualized and Hiệp commenced a search for foreign money from all sources — this became his first collection, marking a crucial milestone in the man’s future trajectory. Once the set of global coins were more or less complete, he switched to archiving Vietnamese bills, especially those from feudal eras and French Indochina.

The history of Saigon via newspaper cut-outs.

At its beginning, some deemed Hiệp’s collecting endeavors “gratuitous” and a waste of effort. To be fair, archival work is an enormous time and resource sink, as he more often than not has to traverse the length of Vietnam on the prowl for artifacts. But to Hiệp, that is just an “occupational hazard” among avid collectors — they are willing to exchange anything, be it material resources or personal gains, to get their hands on precious trinkets.

“There are a few artifacts that I had to save for months to obtain, such as two ‘blocks’ of ancient coins from the reign of Minh Mạng. I call it ‘block’ because they were from 200 years ago and had ‘fossilized’ into a beautiful block. I love them so much. I had to plead to the original owners, promising to pay as soon as I could pool the money, but even then it took months to save up,” he shares.

Life during Saigon’s yesteryears as depicted by the everyday household items in the collection: vintage thermoses, cookie tins, soda bottles. Few items were made of plastic.

Looking around the coffee shop, beside money or electronic device collections, one can also bump into a host of knick-knacks reflecting past generations’ pop culture zeitgeist, like posters of blockbusters, cô Ba soap packages, Perlon toothpaste, Mac Phsu ointment, Con Cọp soda bottles, and the original shop signs of old businesses. To procure these pieces, Hiệp said he had to scour towns in the Mekong Delta, as few Saigoneers today still keep old packages and items.

Hiệp’s fervent passion for antique objects has attracted attention from other collectors and even international juggernauts like UNESCO, which offered him a job in 2004. He’s had rare opportunities to visit many museums and exhibitions to develop his curatorial works. While Hiệp has won a number of records in collecting, he deems the work more of a life hobby. Even after most of his family emigrated to the US, he couldn’t make the move. To him, Saigon historical artifacts are a major part in making collecting a joyful pastime and in living his life the fullest.

From night concert advertisements to a recreation of a living room for well-off Saigon families, these items portray critical points in our collective history.

An unforgettable modern moment

If the outer sections of Lúa Cafe are home to a distant past, the inner space reflects monumental events during the recent pandemic through its selection of unique COVID-era items preserved in glass displays, frames, and thick albums.

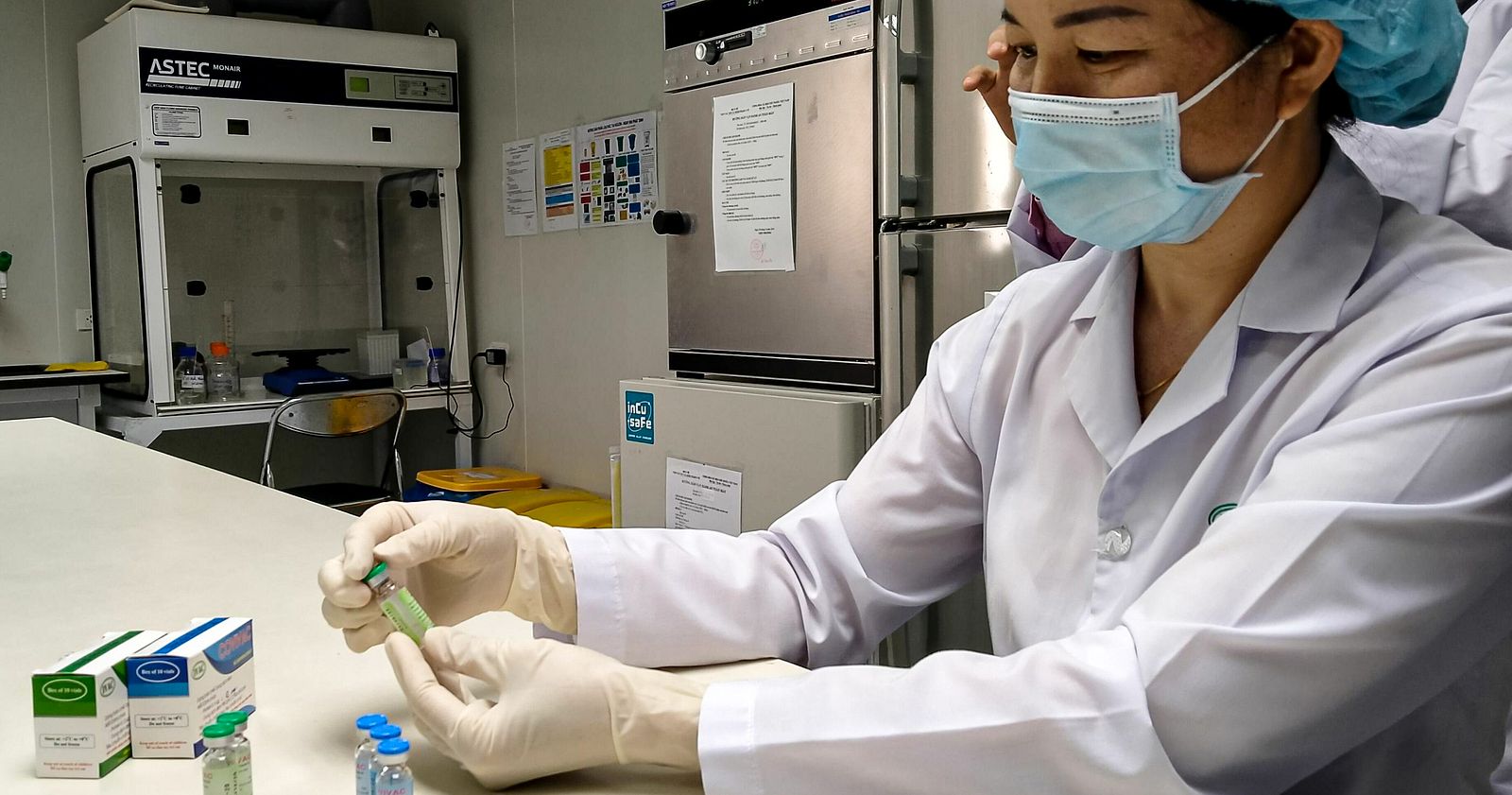

As one of the earliest archivists chronicling pandemic times, Hiệp managed to save a range of tchotchkes, from empty vaccine vials, shopping passes, movement passes, emergency dispatches, to volunteers’ armbands.

Oxygen cylinders and volunteer uniforms tell a gruesome epidemic story.

As a collector, Hiệp’s effort doesn’t stop at claiming the artifact and then leaving it in a corner, he also feels compelled to learn as much as he can about the object to understand its innate value. In the special pandemic exhibition, Hiệp knows by heart every item’s history, who owned it, and how it fits into the big picture.

Only by plunging first-hand into the fight against the pandemic did Hiệp realize that, beneath a deadly silent Saigon battered by COVID-19 waves, there were numerous good deeds done by altruistic Saigoneers helping one another survive an unprecedented global cataclysm. To highlight those efforts was an important reason urging Hiệp to put together this collection.

The pandemic added layers of difficulties on his journey to collect COVID-19 items. For one, he had to rush to retrieve the ward-issued shopping passes as residents tended to immediately throw them away. In the process, Hiệp chanced upon so many unique types of official documents, like a “pass to exercise in public parks” from Tân Phú Ward of District 7 or a “pass to cut grass to feed cattle” from Tây Ninh Province.

Knowing the significance of Hiệp’s archival work, local Saigoneers and even officials participating in pandemic efforts were happy to donate anything he was seeking. Some came in carefully wrapped packages with a hand-written letter dedicated to him, expressing a wish to contribute to this once-in-a-lifetime collection and commemorate those who gave their life for the public cause.

A letter and an armband that a frontline worker sent to Hiệp.

“I wish to gift you these memorabilia from Đà Nẵng during this time when our whole country were busy fighting the pandemic. I wish you excellent health, success in life, and peace of mind,” part of the letter reads. These are the words from Hùng, a frontline official of Thanh Khê Đông Ward of Đà Nẵng.

Through this nationwide item exchange, Hiệp has forged close friendships with people from all over Vietnam, spreading the silvery philosophy by which he’s long lived to many others: When possible, remember to preserve old values, because once they are gone, you can’t get them back.

To honor his efforts, Hiệp’s exhibit was recognized by the Vietnam Records Organization as the country’s most prolific collection of pandemic items. Currently, he’s mulling over a plan to turn these items into an actual exhibition that the public could view.

Hiệp’s own travel permit included in the collection.

As I leave Lúa Cafe, thoughts of Con Cọp-brand soda’s slogan and Saigon’s devastating lockdowns linger in my mind, though I realize that no matter which time period we live in, there are always good Samaritans who do their best to safeguard all things distinctive and valuable about Saigon.