Forming in 2008, with Guitarist Frederico Casagrande, saxophonist Christophe Panzani, and percussionist Tom Poor, Casagrande and Panzani sought to continue a previous partnership in a new band. After releasing their 3rd album this year with French drumming sensation Gautier Garrigue, the group has been extensively travelling the globe impressing crowds and gathering fans along the way.

Related Articles:

- Artist Spotlight: Thanh Xinh

- Zelda Goes To The Gallery: World in My Mind

- This Is What A Mongolian Hip-Hop Video Looks Like

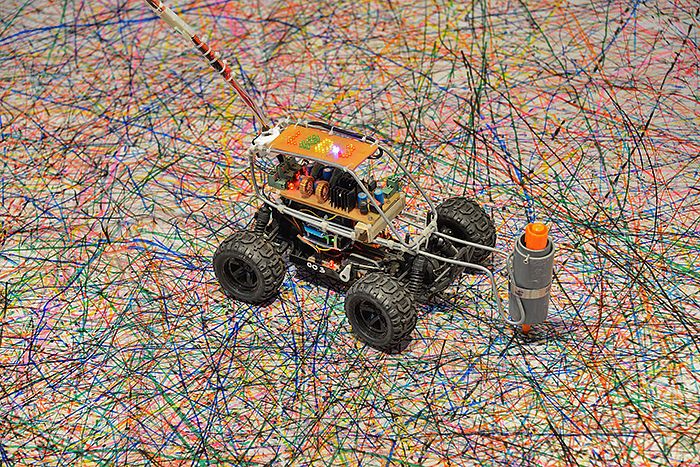

Insignia

When listening to The Drop’s most recent live album ‘Live in Paris’ an untrained ear perplexingly searches for normality and structures that fulfill our waking state. But, The Drops mastery and creativity, fusing jazz with genres of pop and rock, lays most listeners in a space of uncertain laws and unlimited possibilities.

In that obscure void, where reason becomes seemingly unrelated with reality, The Drops find origins for their creativity. In fact, it is no coincidence that The Drops cultivate a listeners’ connection between seemingly unrelated things. The Drops’ first album’s cover depicts an interpretation of Rene Magritte’s famous “Golconda,” letting the viewer decide if the men are rising, falling or suspended.

Relating the abstract to reality in a way that audiences appreciate is an art of its own. I was lucky enough to sit down with The Drops to discuss their process of naming and narrative.

“Some songs have two titles, band title and the real title,” jokes Panzani, “we don’t know which one is the real one. Some of the music, we try it before we have a name.”

One of The Drops’ newest songs ‘Shijuku Gyoen’ received its name “just after a walk in a very impressive garden in Toyko,” says Panzani, “[it] was a tune I wrote in the subway.”

Lacing their reality to musical concepts reveals the depth the trio has in production and reception. “You put together the music for [a] record, you try to listen back to your music as a listener,” says Casagrande. “[We] try to find a story that can link the tunes…It’s hard to put a specific image to it,” he added.

Instrumentation

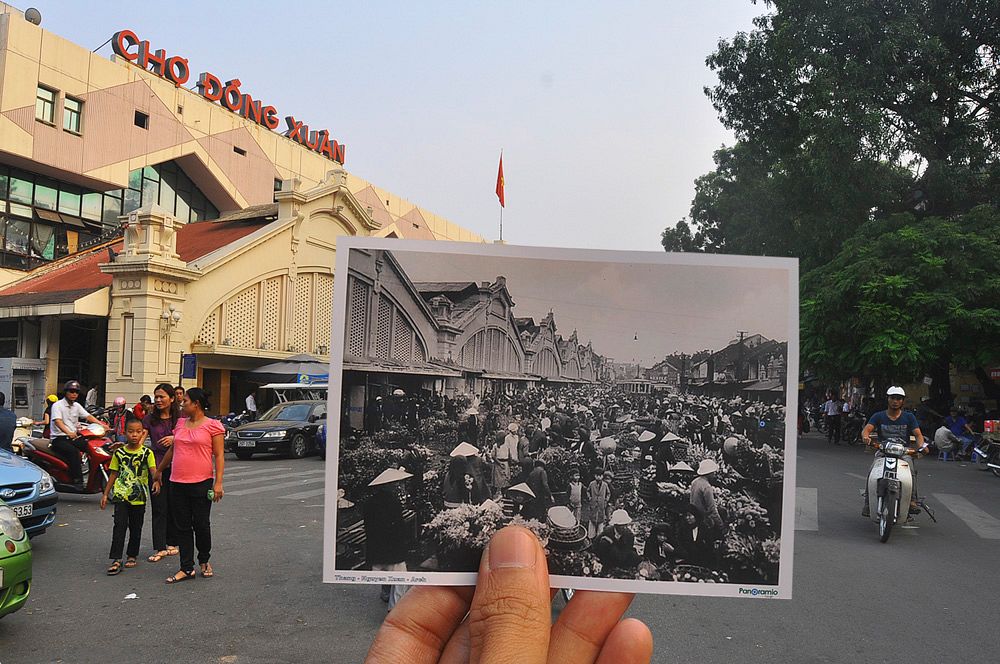

As The Drops stood swimming in their creative space, in a small local venue in Saigon, the audience looked on as if peering at fireflies in a glass jar. Contained in the interplay of cymbal strikes and plucked guitar strings was a dreamscape punctuated by unbroken calls from Panzani’s saxophone. The sound projected by these musicians is meticulous as much as it is unique. The waking dream they lead listeners on is a combination of their talent and their choices.

Most notably is Casagrande’s American Fender Telecaster 62’ reissue. “I bought it when I was 18, and I had a jazz guitar at the time,” Casagrande reflects, “I wanted to sound more modern. And, at the time, I was a big fan of Mike Stern [from Blood, Sweat, & Tears] who had a Yamaha Telecaster copy.”

Mesmerizing the crowd behind the front men was Garrigue. Crunching on top of Casagrande’s overdriven echoing melodies, Garrigue used a combination of Spizzichino Italian cymbals and “a very cheap ride,” he laughs, “but it sounds cool. Especially for this band. I like trashy sounds on the big ride [cymbal].” Sitting back on the couch Garrigue smiles, “I have old Zildjian K’s, but I don’t take them with me,” he jokes, “[they’re] too precious.”

Influence

A translation of Goya’s ‘The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters’ details an artist’s connection between the real and the unreal.

“Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels.”

Goya’s centering on reason as the origin of artistry's allure is highly formalistic. A proscription; “how-to” advice.

In the complex world of Jazz, however, there is a submersion of this order in favor of reactionary jazz pioneers. During his youth, in a small French mountain-town, The Drops’ Panzani received classical LP’s ranging from Sonny Rollings and Coleman Hawkings to Sidney Bechet from his music school as prizes for his achievements.

He eventually explored numerous other legends of American Jazz including Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman. Yet, Panzani believes that “there are so many great young musicians, the scene is growing like crazy. A lot of new inspirations in the saxophone scene and in jazz as well.”

This respect of origin and growth is a connection between player and composition, yet, there is something more at work. “The jazz scene – it’s very individualistic – at the same time it is very social,” says Casagrande, “sometimes we play one spot for one night and with one band [and] that’s it.”

The reactionary spirit of jazz elevates this secular isolation. But, Casagrande takes a different perspective. “When we get together on stage it’s something that’s unified.” He says, “we are in touch with a lot of different influences.”