Why pencils are yellow; the connections between the aviation industry, a centuries-old Central American ballgame and sex; the “true” color of goldfish; the reason we never see Buddha peeing; and the genre-bending decision best-selling novelist Kim Thúy made for her recent book: my conversation with Thúy spun wildly in different directions for over three hours.

This article about it is long overdue. I spoke with Thúy over Zoom soon after Saigon emerged from lockdown last year, and I’ve been unable to do our talk justice ever since. How could I properly capture her brilliant leaps and insights within a simple review of her latest novel, Em? If I pulled too hard on one string of the dialogue, would the entire discussion unravel and drift away? If I dissected it too closely in order to share it, would it no longer be an ongoing source of private inspiration?

Ultimately, it was a passage towards the end of Em that convinced me to press on. To the shock and confusion of her editors, Thúy breaks the third wall and speaks directly to the reader, at one point employing a conversation with painter Louis Boudreault to explain how and why her book is built with threads that weave together and then fray, unwind and only occasionally reunite. She notes that it has “an imperfect ending…scraps and figures drawn from life.”

And that is what I shall do, offer an imperfect collection of snippets from my reading of Em and my discussion with Thúy, not as an imitation of her style (which wouldn’t even be possible), but motivated by it. Thúy notes in her book that its conclusion would be different “If I knew how to end a conversation,” and this article is certainly not an end to my conversation with her or her work, but rather an invitation for others to join it.

“I’m the personification of the word 'luck,'” Thúy says while brushing aside praise for her books and the many accolades they have received. One could interpret this statement in many ways: She has won some of Canada’s top literary awards and her bestselling books have been translated into more than 30 languages in over 40 countries; she survived a perilous journey aboard a rickety boat from Saigon at the age of 10, arrived safely in a refugee camp and was received warmly in Canada; before becoming a full-time writer she earned a law degree and returned to Vietnam to aid in the country’s economic development, and also ran a successful restaurant and cooking TV show. But depending on your definition of luck, I would contend that the luckiest thing about Thúy is how she developed the expansively curious and empathetic view of the world and humanity that comes across in her work.

Photo by Carl Lessard, courtesy of Kim Thúy.

"I never knew France had any involvement in Vietnam" — I read something to this effect in an online customer review for one of Thúy’s books and was immediately struck by the declaration. Anyone with the tiniest familiarity of Vietnam knows about its colonial history, let alone someone who lives here and eats a baguette while strolling past old colonial buildings to an office located on a road named for a French scientist every day. The statement reminded me that the majority of Thúy’s readers do not share the same relationship with Vietnam as myself or the Saigoneer audience. How do our reading experiences differ? Is the book even for us?

My trepidation increased upon reading the description of Em. Another book depicting the war with America and its aftermath via the plights of survivors, refugees and former soldiers? Of course, many great books have been published on these topics, and each brings its own perspective, but after a dozen or so of them, fatigue is understandable; a sense of "I've read enough about this enough already" creeps in, especially amongst those who may have grown up listening to similar first-hand accounts or even lived through the experiences.

Concerns about the book being derivative immediately vanished after a few pages. Em, like Thúy’s previous books, may not stray from familiar topics, but it approaches them with such a unique style, insight and gorgeous language to make it essential. She repeatedly professes to not be a poet, but Em reads like a careful collection of often-connected prose poems. We follow the life of Tâm, a biracial child born on a French rubber plantation who moves from a war-ravaged village to Saigon’s go-go bars and finally the burgeoning nail salon industry in North America. These scenes are eventually paralleled by the plights of two abandoned children who comfort each other on the Saigon streets before emigrating separately. Other characters, including an American helicopter pilot and a French rubber plantation overseer, are depicted in just a few chapters but have large impacts on the plot. There are also people who appear only once or twice, including a rickshaw driver with an appreciation for jazz, a Playboy bunny involved in re-settling refugees, and an eccentric millionaire who “offered his clients virtual spaces were the rules were set by fantasy and love, by gambling.”

Em is a very quick read that tells a story far larger than its page count thanks to Thúy’s gift for packing an incredible amount of meaning into a few words or details. She offers philosophical truths in compact lines when detailing characters’ motivations such as “love, like death, need not knock twice to be heard.” Similarly, she can create a fully realized person or scene in only a couple of details. For example, a street kid who investigated leftover bowls of noodles and “learned to read the customer’s personalities. He guessed who warmed their taste buds with powerful chili pepper so that their tongues could spit words of fire at their unfaithful spouses. He could distinguish which drops of sweat on the side of a face were caused by hot broth, and which were incited by nervousness.” The book’s patchwork construction that shifts abruptly between characters and topics may not be for everyone, but those that appreciate works that challenge the concept of what constitutes a novel will find plenty to savor in Em, as will anyone that admires great sentence-level writing, regardless of how many times they think they have heard similar stories.

The cover of Em (Australian version) via Penguin Books.

Another interesting element of the book’s format is the insertion of passages of pure fact and history. Readers encounter the origin of the word "coolie"; The Birds actress Tippi Hedron’s happenstance introduction of nail polish to the Vietnamese diaspora; and the invention, use and effects of Agent Orange, amongst other things. These sections read like tiny footnotes scavenged from well-written history books and, in addition to providing interesting tidbits of information, serve to anchor the characters in the real world and further entrench them in a true and amazing timeline where unseen connections are constantly at play.

“If you have one million soldiers, you have 10 million stories,” Thúy tells me. Her book attempts to tell just one of them. This mission is put into perspective when considering how many people died in the war. At the end of Em, Thúy states that 58,177 Americans died, while 1.5 million military personnel and 2 million civilians in North Vietnam and 255,000 military personnel and 430,000 civilians in South Vietnam lost their lives. She explained that she compared the numbers to highlight how America knows the exact number of its dead, while Vietnam must estimate and thus, “A poor country cannot even count its deaths.”

How many lives are ignored when rounding such figures? If one life is 10 stories, do the math — that could be millions of stories. And as Thúy noted, unlike other nations, Vietnam doesn’t have any famous monuments for these “forgotten soldiers.” They are simply lost to time. Thúy’s work, its amalgamations of fact, fiction and partial lives seems to me to be such a monument. By reading Em we honor those that never received proper recognition, nor the opportunity to share their experiences and mourn the stories that never had the opportunity to be told.

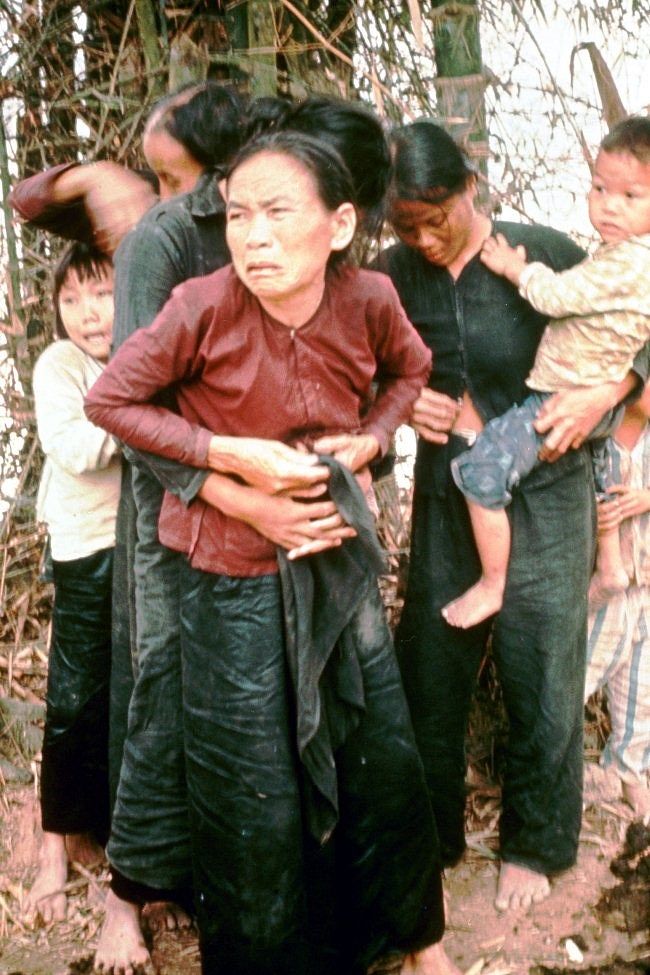

Photo by Ronald L. Haeberle via Wikimedia.

The interplay between fact and fiction is one of the most unique elements of Thúy’s work. Early in the book, Tâm finds herself in Mỹ Lai during the infamous slaughter of civilians by American soldiers. At one point a military photographer takes a photo of her and several other characters posed, I immediately realize, almost exactly like the famous photograph. Then, a US helicopter pilot comes to their aid, aiming his guns at his fellow soldiers, just as happened in real life. But soon fact and fiction peel away from one another. The people in the photo do not live the rest of their lives like the ones in Em. The heroic pilot’s future in the book differs from that of the real-life pilot, and I learn later that he experiences events that actually happened to a different, real-life person. Elsewhere, we are provided details and impossible-to-know inner thoughts of historical figures such as Naomi Bronstein, a Canadian who devoted her life to sick and orphaned children in foreign countries and was instrumental in Operation Baby Lift.

Upon initial reading, I was troubled by this mixing of fact and fiction. I didn’t know why Thúy did it. Were there ethical concerns in doing so? What would real-life individuals think about being fictionalized? Does playing with the truth risk confusing readers about the actual history, or in any way diminish it? I knew it was very much an intentional, artistic decision but I didn’t fully understand it.

“I’m weaving different true stories together because I don’t have enough time to tell the story of each character individually; how do I get to tell so many stories under one story? So that’s why I gave myself the freedom of fiction; to weave these many true stories,” Thúy said simply when I brought the issue up to her. She then went further and admitted that the timeline of the story doesn’t line up correctly with the characters’ ages and true events, and to her, it doesn’t matter. She leaves dates, full names, places, and other details out of the book to underscore that it's a work of fiction. Ultimately, any deviations from the truth don’t matter to her because she isn’t giving a lecture about history but rather telling a story “about emotions” that were very much real for many people at the time. And sometimes the truth is more unbelievable than fiction and impossible to fabricate which is why she borrows from it.

When pressed about what would happen if she met one of the people she fictionalized or their family, such as the American helicopter pilot, she said she hoped they would be flattered by her work. She inserted his real story into that of a fictional character to “pay homage to a moment of his life” that she considered to be an instance of a person exceeding what it means to be human. Thúy believes that each life contains many lives which helps explain why she compiles singular, true moments or vignettes to build a character.

In Ru, Thúy’s first novel, she includes a scene with a family based on a real-life encounter. After its publication, Thúy had the opportunity to meet the child she had described and he corrected her on the name that was used for his father. But the boy wasn’t upset, and Thúy wasn’t troubled by the deviation from the truth, partly because the truth is slippery, especially when considering the role of imperfect memory and perspective as alluded to at the beginning of Em: “If your heart shudders on reading these stories of foreseeable madness, unimagined love, or everyday heroism, know that the whole truth would very probably have provoked in you either respiratory failure or euphoria. In this book, truth is fragmented, incomplete, unfinished, in both time and space. Then is it still the truth? I’ll let you reply in a way that relates to your own story, your own truth.”

It was at this point in our conversation that Thúy turned philosophical and began to question what exactly is truth. To illustrate the idea that truth is not universal, she makes a surprising jump and begins to talk about goldfish. The name seems obvious in English: their scales are golden in color. Yet the French term, poisson rouge, translates to “red fish,” suggesting a different definition of colors or available vocabulary. Meanwhile, a now-rarely used term in Vietnamese, cá Tàu, refers to them as “Chinese fish,” which ignores color altogether, and instead uses the fish’s origin as its defining feature. If the world cannot agree on a fish, what chance is there to reach a consensus on the truth of more complicated matters related to war and shared histories? With this in mind, Thúy considers it less important to try and adhere to any empirical truths and more necessary to stay true to broader themes and personal truths while keeping an open mind to what others consider true.

Thúy’s approach to truth and its role in literature helps also explain another question I had while reading Em regarding chance. The number of times and the profound ways in which the characters continually cross paths with each other seemed at first unbelievable. But after talking with Thúy and getting the smallest peek into how her brain works, it makes sense. “Everything is linked together,” she says before tracing current global shipping delays to container ships whose importance increased during the war with America. She then notes how Japanese electronics became popular in the West because all the containers that brought weapons, supplies and vehicles to Vietnam needed to be filled for their return journey to manage costs. The popularity of the products then increased the pressure for the war to continue. And when it finally did end, western companies were compelled to find new and different markets, namely China, to send exports to. Such staggering connections put into perspective the odds of people in her book meeting one another numerous times in their lives. To underscore the point, she says she believes everyone has less than six degrees of separation and because she was recently on stage at an event with Canadian Prime Minister Trudeau — I am now connected to President Obama via her in just three steps.

Photo by Chick Harrity via the Hanford Sentinal.

But more than just her talent for revealing the interconnectedness of lives and events, Thúy’s gift for finding beauty and empathy in any situation propels Em. When she came across a photo of two young street children — one of whom is in a cardboard box — holding hands 15 years ago, she knew she wanted to write it into a love story because during “misery, you have the purest expression of love. That is the problem of us humans, and this book is about that; we are generous at the same time we can be the cruelest person.” Thus love that reaches across enemy lines and expands in the darkest of moments against a backdrop of great cruelty and suffering lie at the emotional core of Em. For other authors, such a move might seem disingenuous or saccharine, but Thúy is uniquely able to find humanity amidst great savagery. As she says, “I really only want to share the beauty of things. The beauty of us as humans. We are so amazing from the bad to the great. We are crazy! … When we are good, we are so good, and when we are bad, we are so bad. Between the two we have so much to say. For me, it's that fascination with humans.”

Of all the many morsels of wisdom and perspective-altering observations that Thúy shared, the one that sticks with me the most came via a conversation she had with a scientist. The individual noted that NASA regularly works with philosophers when researching space because, at that level of complexity, one needs the mind of someone who can ask questions of the unknown. The scientist then explained that people like Thúy are constantly searching to learn more because “knowledge is the only form of infinity that a human can experience… hat we can touch.” Picking up Em is therefore a means to come into intimate contact with the infinite depths of history, humanity and emotion.