Nguyễn Quang Thân passed away on March 4, 2017, several weeks before I moved to Saigon. So of course I never met him, but I feel like I know him. My first introduction was via An Insignificant Family, the fictionalized memoir written by his wife, writer Dạ Ngân, which includes a description of the 10 years they spent apart, writing letters to one another from opposite ends of the nation, followed by their life together. In the years since I first interviewed her about that novel, I’ve been blessed to be adopted as her son; one of the greatest gifts of my life. No visit with her goes past without him being mentioned. For years, Nguyễn Quang Thân has simply been Ba Thân.

Photos of Nguyễn Quang Thân from Dạ Ngân's personal collection.

How to review a close one's creative work?

Since first speaking with Dạ Ngân at the living room table where she shared so many meals with Thân, I’ve met his sons, brother, and sisters; and visited his former homes in Hải Phòng and Hanoi. I saw the balcony where he raised pigs during the nation’s poorest times, gazed across the park near his office he would walk through every afternoon while taking a break from writing articles, and of course, traveled to the sites most important to him and Dạ Ngân: the Vũng Tàu veranda where they first met at a writer’s conference in 1983; the pagoda where they first kissed; the bridge in Cần Thơ where he cycled back and forth looking to recognize her clothes on a drying rack (and later memorialized in a poem I helped translate). I’ve been told his many jokes and wordplays; anecdotes about how he traded those pigs he raised for a motorcycle and confounded train staff in Europe; and the many views, mannerisms, memories, habits and preferences one collects about the people close to them. Learning the simple, intimate details of a person, such as knowing he likes to put fresh durian in his coffee or observing the humble ingenuity of the fabric hanger he made from twine and a PVC pipe can feel like reading pages from their diary

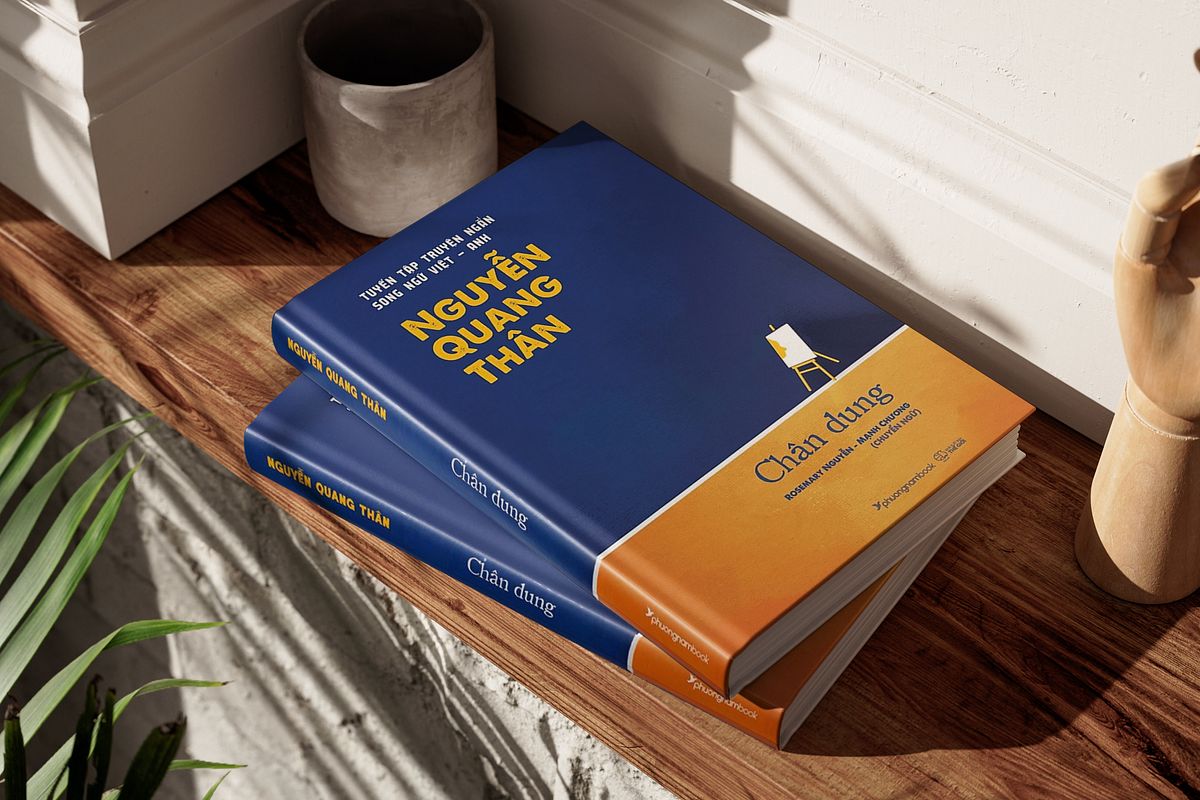

I offer this personal preamble to explain why writing this review of Chân Dung, a bilingual collection of his stories released last month, has been so difficult. How could I possibly separate the man from his work? How could I present an unbiased appraisal of the book that fits within the appropriate parameters of a review? Then I began reading, and all became effortless. The stories are works of their own vitality and power because of Thân’s prodigious imagination and keen desire to understand and describe the world around him without relying solely on his own experiences. This trait matches the way he was first introduced in An Insignificant Family; as having “the avid interest of a small boy who has just arrived in his promised land.”

Novels and short story collections written by Nguyễn Quang Thân from Dạ Ngân's personal collection.

Each of the five stories in Chân Dung was written and set in the mid-1980s and early 1990s and offers glimpses into the culture, daily life, concerns and preoccupations of the time via the experiences of ordinary individuals. A talented painter, a poverty-stricken widow, a rural nun, a disillusioned divorcee, the son of a high-ranking party member, the daughter of a hired driver and the lecherous wife of a wealthy businessman are among the characters readers will meet. The stories find many of them at important but not necessarily climactic moments in their lives, when they learn something about the world and, by extension, themselves. When reading the stories more than 30 years after they were written, some of the scenarios and details seem strange and distant but the themes of lust, loneliness, morality, and greed remain fresh, particularly when presented by a voice wise enough to know when to make a sly joke and slip laughter in amongst the tears.

Biting social commentary from a keen observer

Chân Dung offers numerous criticisms, mainly of society’s emphasis on wealth and official position over actions and character. This judgment is most overtly witnessed in the contrasting behavior of a chauffeur and his boss in ‘Thanh Minh.’ The chauffeur’s career is limited by his previous employment by the French, while the local official enjoys a series of promotions despite a dearth of intellectual curiosity and thus relies on his chauffeur’s knowledge of art and history to get ahead. The chauffeur’s daughter is denied books and movie screenings because her father is not ranked high enough in the party, while the official’s son fails upwards to a college degree and a comfortable job despite never studying. There is no justice or comeuppance in the story, and the struggle for position continues after death, via the corrupt and politically motivated squabbles over burial sites determined by cadre ranking. Still, the narrator offers the resigned hope that in the afterlife “our individual lives will dissolve into one another, to be re-formed into new and different entities which will be more suitable to that eternal world. Hatred and debt will be erased, leaving only love.”

Thân earns the right to criticize society because he expresses a sincere love for it and his fellow citizens in the stories.

The searing depictions of the upper class continue in ‘The Waltz of the Chamber Pot.’ The narrator, an unlucky intellectual, escapes poverty by working as a servant in the home of a rich woman. His position allows him to observe her engage in a series of extramarital affairs with men representing different archetypes of society including an old, lecture-prone professor who pontificates on the concept of “New Women” and publicly denounces Hanoi fashion as being too revealing while requesting his mistress wear a two-piece bikini from Thailand. When he is unable to satisfy her in bed, he blames everything but himself, including her western lingerie that “confused” him with its two openings — “nothing but a luxury product typical of the whole blasted system of democratic capitalism.” She replaces him with a young “bourgeoisie capitalist cad,” whose bawdy jokes, British liquor and masculine vitality quickly lose their appeal; he is revealed to be a boring, hollow example of nouveau-riche vapidity that would go so far as to manipulate the entire city’s hột vịt lộn market just to show off. Even her husband, a powerful merchant, is a cruel and vindictive man who views his wife as a commodity to be acquired via shows of power; the power he was given by a society that includes the underemployed intellectual.

Thân earns the right to criticize society because he expresses a sincere love for it and his fellow citizens in the stories. Often, natural settings serve as stand-ins for the objects of his affections. Readers grasp his sentiments for his nation via descriptions such as: “Under Mother’s direction, the whole family pitched in to break new ground for a garden along the banks of the stream; there was the sound of washing the uncooked rice in the morning, the sight of the runoff from the hard kernels flowing down the riverbanks like milk. Laughing thrushes warbled their song from behind the guava trees that Mother had planted.” It’s images like this and declarations such as “the truth of the cloud was really the rain,” that assure readers that a thoughtful and caring individual is observing the world in which he occasionally points out flaws.

Original publications of two of the stories compiled in Chân Dung from Dạ Ngân's personal collection.

Words from an empath

The satirizing of the rich and powerful is effective in part because Thân offers an alternative. The stories take a tender, forgiving approach to the poor with particular praise reserved for artists and scholars. In ‘The Portrait,’ a painter has the unique gift of depicting an individual in a way that reveals their soul. His life lacks extravagances and he expresses no desire for fame or high position, instead taking delight in the simplicity of an old water kettle and the doting presence of his niece. The serenity he enjoys as well as the love of family and friends suggests to readers that this is an example one should follow, for not only personal happiness but to achieve a just and harmonious society. This story, in particular, is one where I had difficulty separating the work from the writer. It reminded me of how Thân lived humbly and was happiest when his home was filled with the laughter of his family and friends who were writers, artists, scholars and musicians.

Despite the moments of scathing ridicule, the stories are not overly moralizing. Love and lust, in particular, are complex human realities presented plainly, not so readers can deem actions right or wrong. For example, In ‘An Autumn Wind,’ the protagonist has a sexual encounter with a rice wine maker as a way to thank him for supplying her abusive, alcoholic husband with the liquor he desperately demands, but refuses to work for. Her action is not seen as a matter of moral failure but rather an example of the unenviable realities that come with poverty and bad luck. Readers will come away from the book with an unwavering belief that unfortunate people should be viewed with empathy and we must remind ourselves that we cannot know what private miseries and hardships a stranger is shouldering. This applies to the characters in ‘The Woman at the Bus Stop’ as well. In this short tale, a man and a woman — who have both been treated badly by lovers and left with nothing but a distrust of the opposite sex — meet and forge a bond out of desperation. The ending, which I will not spoil, offers a powerful comment on the extent to which human generosity may offer solace and solution.

Further securing Thân’s rhetorical position as a qualified commentator on the state of the world is his frequent allusions to works of literature and history.

Further securing Thân’s rhetorical position as a qualified commentator on the state of the world is his frequent allusions to works of literature and history. Naturally gifted with languages, Thân knew French, taught himself Russian and English and was well-read across cultures and genres, as evident in his sprinkling in a variety of allusions such as Konstantin Simonov’s poem ‘Wait for Me,’ and Alphonse Daudet’s ‘The Stars.’ These are helpfully noted in the footnotes along with other necessary and interesting references such as Văn Mười Hai, the operator of a notorious pyramid scheme in the 1980s. Elegantly translated by Rosemary Nguyễn and Mạnh Chương, the book reads naturally in English and presents no difficulties in contextual understanding for those with moderate knowledge of Vietnamese history and culture.

By the time this review is published, I will have asked Dạ Ngân about some of the “behind-the-scenes” details for Chân Dung, probing for the inspirations for the stories and characters as well as inquiring about what she remembers from that time — Did he send her drafts? What did he say about each? Did his editors demand he change any details? But like you reader, at this moment, I don’t have or need any of those details to fully admire and appreciate the wit and generosity of each story. And you are like me in the fact that I’ll never get to sit down and have a conversation with Nguyễn Quang Thân as I’d wish. But through his writing, he will live forever and can continue to share his imaginative understanding of the world.