The Immolation first came to me as a bewildering surprise: at a now-relocated bookshop in Singapore, the book caught the eyes of the 17-year-old me. It was not so much the cover’s pale blue background, or the expression of ennui on the author’s post-impressionist portrait, but rather its dealing with the American War. After all, the title directly referenced the iconic protest by the Buddhist monk Thích Quảng Đức, who set himself on fire on the street of Saigon.

Written by Chinese Singaporean writer Goh Poh Seng, The Immolation was first published in 1977, and republished in 2011 by Epigram Books. A note on the its setting: even though the country name is never mentioned once in the book, the proper nouns’ orthography, as well as mentionings of US presence amidst jungle battlefields and bars in the city-capital, etc. are ostensible nods to real-life Vietnam as the novel’s (unnamed) Southeast Asian country setting.

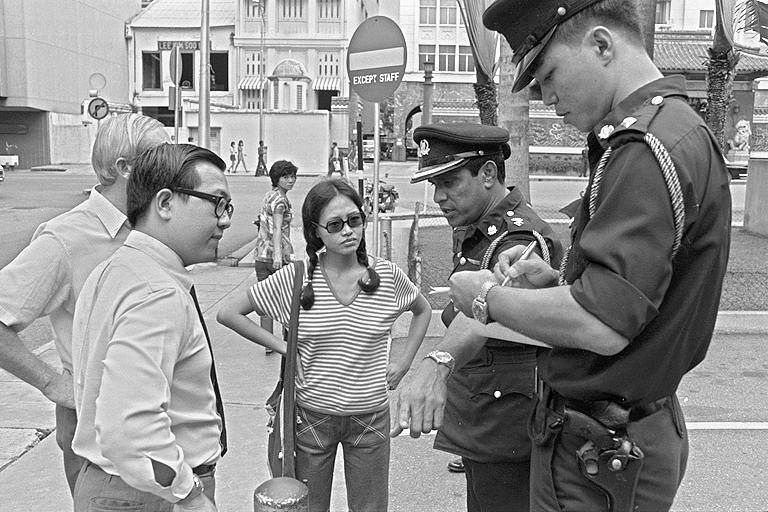

Francis Khoo (left), a lawyer, was among 150 people who staged a demonstration outside the US Embassy at Hill Street, Singapore in 1973. Together with Professor Daniel Green (hidden) from Nanyang University and Lap Choo Lin (center), a University of Singapore graduate, they presented individual petitions to US President Nixon. They were protesting against the bombing of North Vietnam by the US. Image via National Archive Singapore.

The Immolation centers around Thanh, a doctor-turned-wannabe-poet who returns to Saigon after having studied abroad in Paris. He joins the guerilla National Liberation Front (NLF) with his diverse cast of peers, while being haunted by the sight of a monk smiling as he sets himself ablaze, and his relationships with friends, particularly his love interest, My. Through the course of the story, Thanh questions what it means to live and die for a political cause. Henceforth, the novel is a bildungsroman — a literary work focusing on a character’s journey to maturity, and an ambitious one at that — as it demonstrates Goh’s attempt at tackling postcolonial issues set in a country different from his own, while also articulating existential concerns through the eyes of relatively young, idealistic people.

Sensitivity to Vietnamese culture and historical details

I am pleasantly surprised to see Goh approaching Vietnamese culture and historical details with much sensitivity, amidst the host of English-language media at the time centering the western perspectives towards the American War. One can’t help but wonder what specific research processes Goh has taken to write a novel with empathetic engagements with Vietnamese elements.

Through his characters, Goh waxes lyrical about tangerines in the Central Market evoking the festivities of an incoming Lunar New Year, “black, broad-backed” water buffaloes having a bath alongside squealing children in the countryside, or fish sauce: “its heavy, tangy taste was something so age-old, so familiar as to be part of the people of his country […] Without it, no local meal could be considered complete.” He focuses on the struggles of the Vietnamese in wartime, writing about simple spears and booby traps, but also the Vietnamese landscape. “We sometimes forget how beautiful our country is,” My comments. “[We] only remember the fighting; we only see the suffering, […] the beastliness and the evil. [Some] day, after the victory, our people will inherit peace and this beautiful country again.”

Thích Quảng Đức self-immolates in Saigon to protest religious discrimination in 1963. Photo by Malcolm Browne.

A number of historical details are thoughtfully inspired and embedded into the novel. History lovers might recognize Goh’s vivid references to the 1960s student demonstrations against the regime’s dictatorship and US interventions, the 1968 Tet Offensive that includes a brief attack on the Presidential Palace in Saigon, and of course the Buddhist crisis that peaks at Abbott Thích Quảng Đức’s self-immolation. Particularly memorable is a scene where the characters hide inside a bomb shelter: “Thanh huddled in the darkness, his body flexed, his chin resting on his knees, foetal in the womb of earth. The earth smelt of dampness. Even with all that noise, he thought he could hear water trickling, like lilliputian drumming.”

“Thanh huddled in the darkness, his body flexed, his chin resting on his knees, foetal in the womb of earth. The earth smelt of dampness. Even with all that noise, he thought he could hear water trickling, like lilliputian drumming.”

Some historical facts and names of certain characters and locations are, however, imperfect. For instance, it can’t be fully verified if NLF fighters ever conducted espionage in bars, nor the extent to which some of them would elope from their missions. One also wonders whether the spellings are changed in service of Singaporean readers more familiar with the Latin orthography of English and Malay; some names are spelled “Kao” and “Thing Hoai Pagoda,” words that don't exist in Vietnamese. These inaccuracies nevertheless, should not be interpreted as defects in and of themselves. Instead, taken as a whole, I recognize Goh’s respect for and desire to understand more about Vietnamese people and happenings. It seems that his characters, especially Thanh, act as vessels for Goh himself, or any non-Vietnamese readers, to acculturate into the Vietnamese setting — observing first-hand, being amazed by the Vietnamese scenes, while empathizing with Vietnamese guerilla fighters’ experiences.

Nuanced characterizations and the irony of ideological wars

Literature professor Dr. Ismail S. Talib, who wrote the preface to the edition, discusses Vietnam’s geo-political importance as an iconic battleground for post-colonial ideologies and its relative distance from Singapore, and how they are possible reasons why Goh decided to implicitly set his novel there, while exploring themes concerning post-colonial Southeast Asia at large. His cast of Vietnamese characters is diverse and nuanced, exemplifying the different kinds of people with their own reactions and rationalizations to wartime political causes.

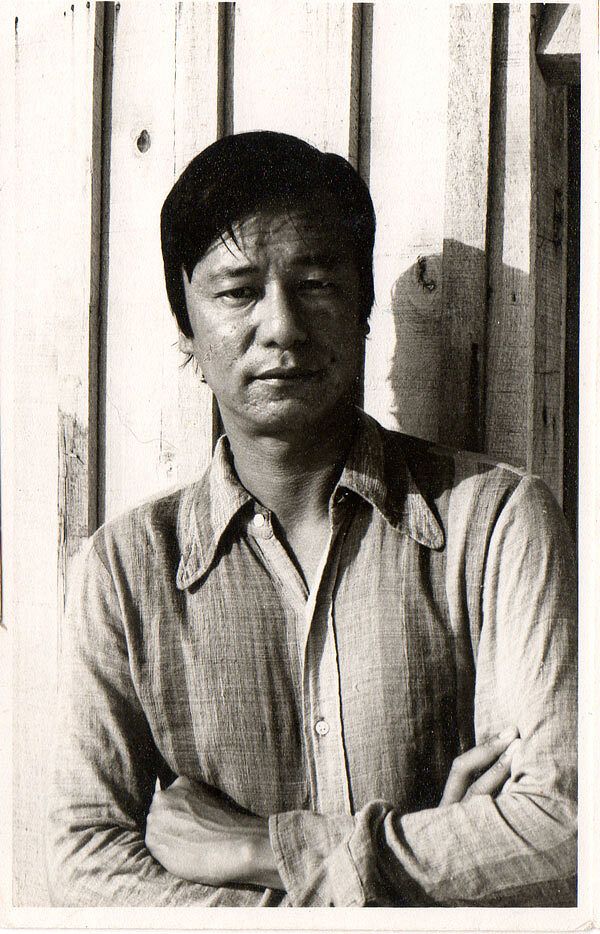

Goh Poh Seng was a Singaporean novelist and physician. Photo via Wordpress.

In contrast to Thanh’s brooding uncertainty, his best friend Quang Tuyen is a pragmatic and optimistic journalist with a c’est la vie attitude towards wars and their dilemmas. Meanwhile, his love interest My is a fellow student whose personal sufferings become the catalyst for her idealistic and dogged support for the guerilla’s efforts — she even often chastises Thanh for his constant doubts. It is lovely to read about the cheeky and sincere dynamic between the two friends, and, likewise, the lovers’ earnest yet tricky relationship from Goh’s beautifully crafted dialogues. There are also those like Kao, a peer whose words twisted ideologies in his selfish favors against Thanh himself; Thanh’s father Monsieur Vo, who wanted to shelter his son from joining the guerrilla despite being aware of the government’s corruption; or fellow sympathizer Xuan, who's facing doubts on whether to support the cause fully or protect his family. By constructing characters as diverse individuals across backgrounds, characteristics, and degrees of involvement in a political cause, he rebukes views of revolutionaries as one fanatical monolith blindly devoted to a movement, or those harboring doubts towards it as cowards. Ultimately, perhaps Quang Tuyen says it best: “Just because I am joining the Cause, doesn't mean that I agree with everything […] One reason I'm fighting is that I want the right afterwards for more of our people to be human beings.”

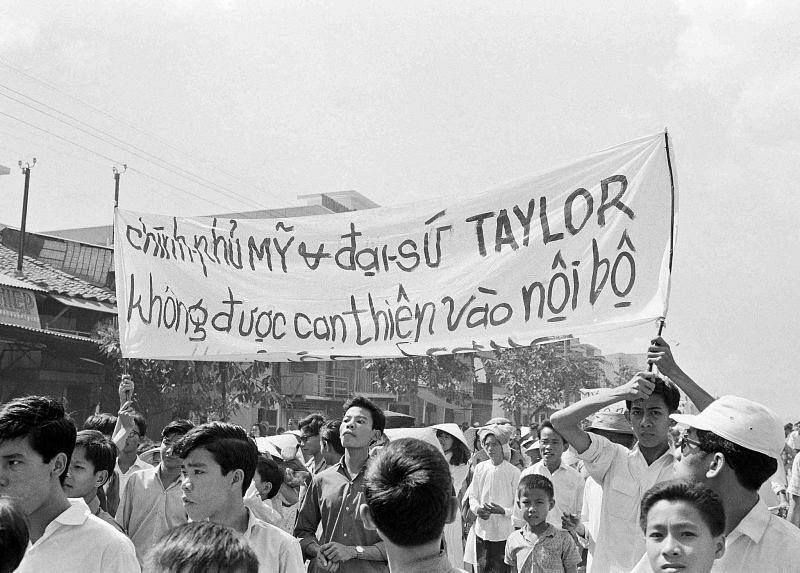

Students march to decry US involvement in Vietnam in 1965. Photo by AP.

It then might be difficult to classify the book as either in support of or against communist guerrilla warfare in Vietnam. Vietnamese readers should not be expected to find a concrete unwavering message of devotion, from frustratingly transient character arcs to an ending that leaves them at an ambiguous cliffhanger with none of the senses of triumph, and a reflective yet indecisive main character with arguably bourgeois and defeatist tendencies: “After the bloodshed, would anything be written on that page?” Thanh ponders. “No, there will be nothing. […] This battle would not even make it to the footnotes of any future history written about their time. No one would know. Probably no one would care either…”

Nonetheless, a great number of examples of Vietnam’s war literature, notably those produced post-reunification, are not too different. From Lê Lựu’s satirical A Time Far Past to the famous The Sorrow of War by Bảo Ninh, these works, while different in their tonalities, strip away the need to reinforce reunification’s feelings of triumph, and instead focus on war traumas and systemic post-war struggles. The Immolation exemplifies Goh’s sensitive foresight to the human condition, acknowledging the desolation of war, but also larger existential themes, such as the ironic freewill that might liberate us from one suffering… to another, yet remains the part and parcel of life.

The Immolation exemplifies Goh’s sensitive foresight to the human condition, acknowledging the desolation of war, but also larger existential themes, such as the ironic freewill that might liberate us from one suffering… to another.

All in all, with such ambivalence and bittersweetness, The Immolation will not attempt to offer readers a definite view of the American War nor a solution through a tumultuous socio-political landscape. “Words. They do not expiate. Nothing can do that,” Goh wrote self-insertingly. “But they make you a little healed, whatever you’re suffering from, or rather the real thing you’re suffering from: man disease.” At this point, it has been my second time reading the novel. Compared to his previous debut novel, If We Dream Too Long, The Immolation has unfortunately not garnered much attention in Singapore or Vietnam.

Maybe I’ve been waxing poetic over this book. I am aware that I might have put the book on a pedestal as a Vietnamese person residing in Singapore, a country already without much overt historical or cultural relations with where I originally come from, compared to its more immediate neighbors. The Immolation, as a novel dealing with political strifes that come with nation-building in Southeast Asia at the time, now becomes, to this reader, a sentimental emblem of shared regional concerns, characterized by empathetic appreciation, and a vision towards an interconnected and, even if idealistic, universal human experience. Perhaps by writing with each other, and reading for each other, a book is no longer a Singaporean novel, nor a Vietnamese one, but a novel we can call ours.