“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.” This quote from Shakespeare’s Henry IV basically sums up the political climate of Vietnam in 1883. In that year alone, four different men played the part of the Emperor of Vietnam—none to critical acclaim.

First was Emperor Tu Duc, who had ruled Vietnam from 1847 until his death in July 1883. He was succeeded by Emperor Duc Duc, who spent a measly three days on the throne before getting ousted by Emperor Hiep Hoa. Emperor Hiep Hoa was no marathon man either, as he lasted only four months in the leading role before being cast aside by Emperor Kien Phuc in December 1883.

There are countless reasons as to why the royal ground was so shaky in 1883, but two of them stand out. The first and obvious reason was the fact that Emperor Tu Duc didn’t produce any direct understudies to the crown. The second and probably more important reason why Musical Thrones was so popular in 1883 could be attributed to two royal advisors who were behind the scenes—Nguyen Van Tuong and Ton That Thuyet.

Both men had been appointed by Emperor Tu Duc and after decades of service, they had accumulated considerable influence over the royal court. Aside from their own ulterior motives, they were also frightened to death by the growing French presence in Vietnam. Nguyen Van Tuong and Ton That Thuyet were educated mandarins who clearly saw the score: as France’s power went up, their power went down.

So in 1884, after essentially appointing and deposing three emperors in rapid succession, Nguyen Van Tuong and Ton That Thuyet felt like another change was in order. Instead of revising the script, both men decided that a simple recasting of characters would suffice. This was when Ham Nghi, a boy who was barely 13, was thrusted into the spotlight, the crown placed upon his head.

Related Articles:

Ham Nghi was the younger brother of Emperor Kien Phuc, but he didn’t live or grow up in the royal courtyard. Actually, it is believed that he lived in relative poverty outside of the palace walls in the imperial capital of Hue. The two royal advisors liked Ham Nghi in the role of Emperor because he was young and therefore, more likely to yield to them. But, just like his brother and the few kings before him, Emperor Ham Nghi didn’t get to run Vietnam for very long; in fact, within a year, he would be on the run.

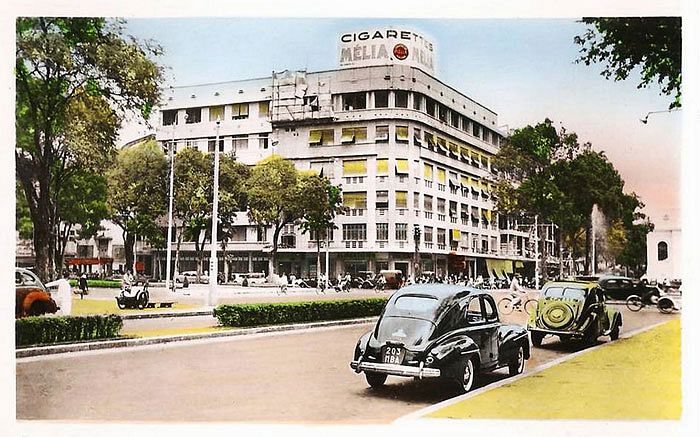

The Hue Imperial Citadel.

In July 1885, during a ceremonial visit to Hue, a contingent of French troops was ambushed by thousands of Vietnamese. Outraged by this premeditated act, the French took revenge by looting the royal palace a few days later.

Before the entire palace was seized, Emperor Ham Nghi and his advisor Ton That Thuyet were able to escape, fleeing to the mountains near the Laotian border. It was here that Emperor Ham Nghi issued the edict known as Can Vuong (Loyalty to the King), which was basically a call to arms to expel the French and restore the Emperor back to the throne.

At its inception, the Can Vuong Movement was a modest success. Even though he was living like a nomadic bandit, Emperor Ham Nghi was able to appeal to a large segment of the population. Attacks on French troops and bases were widespread throughout central Vietnam and when supporters couldn’t find anything French to lash out at, they targeted Vietnamese Christians (whom they saw as French allies).

After centuries of colonial exploitation all around the world, the French knew they couldn’t afford to let the Can Vuong Movement escalate. In 1887, they amped up their forces and struck back at the movement’s supporters. A year later, the French finally caught up with Emperor Ham Nghi and arrested him. This effectively ended the Can Vuong Movement since there was zero chance that Ham Nghi would ever play king again.

The capture of Ham Nghi.

Instead of executing him, the French decided to exile Ham Nghi to their African colony of Algeria. Historians believe Ham Nghi was spared because he was only 17 years old and might come in handy at some later date. (They were masters of colonialism, after all, and they had seen this sort rebellion in other places.)

Ham Nghi would spend most of his remaining years in Algeria. He married a French Algerian woman (pictured in the article's opening photo), had a few kids, and when he passed away in 1943, Ham Nghi was buried in southern France. In 2002, Vietnam sent a delegation to France to request that his remains be exhumed so that he could be reburied in Vietnam. That request was denied.

Ham Nghi is still remembered as the boy emperor who spearheaded the Can Vuong Movement in the fight against the French. His remains may not be in Vietnam, but he remains an essential figure in Vietnamese history, his life full of sound and fury like something out of a Shakespearian play.

About the writer:

California is where he’s from, Saigon is where he’s at and this column is where he could be found. If you’re looking for a freelance writer specializing in Vietnam, please contact Vinh at vinh@berkeley.edu.

[Photo of Hue via Khnah Hmoong]