France left a diverse legacy in Indochina: colonial buildings, flushing toilets and even the bubonic plague.

In 1897, failed French Minister of Finance Paul Doumer took up the post of Governor-General of Indochina, hoping to turn his career around, according to Atlas Obscura.

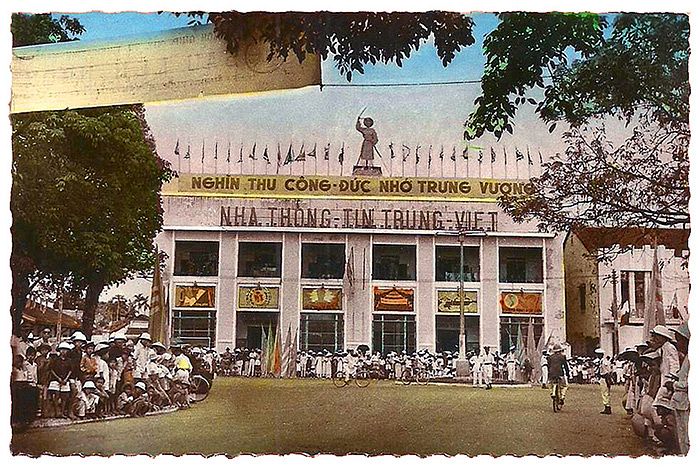

French Indochina was a collection of colonies made up of what now includes Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Doumer deliberately chose Hanoi to serve as the capital of this region and to become an emblem of French civility in Southeast Asia.

Delighted that he wasn’t expected to rebuild an entire city – as was the case with chaotic and unruly Saigon – Doumer set his sights on modernizing the already established Hanoi.

A portrait of Paul Doumer.

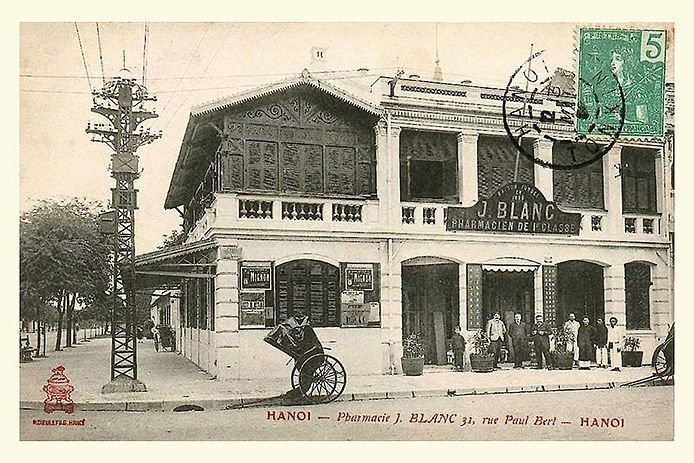

Paying tribute to his native France, the Governor-General outfitted Indochina, especially Hanoi, with French-inspired infrastructure. At the turn of the century, colonists enjoyed tree-lined streets, airy villas and, of course, Western toilets.

A state-of-the-art sewer system was constructed beneath Hanoi’s new quartier européen, whereas a smaller and significantly less hygienic model ran beneath the quartier indigène. The insufficient sewer system in the overcrowded Vietnamese neighborhoods was subject to backflow during the rainy season, flooding the streets with human waste. The more modern section of the sewer system was considered a success.

This achievement was considerably diminished, however, when rats started scurrying out of the drains in Hanoi’s colonial homes.

Doumer’s government outfitted Hanoi with over nine miles of sewage lines, and these pipes functioned as the perfect breeding ground for rodents.

If rats popping up in Hanoi’s swankiest toilets wasn't enough, cases of bubonic plague began to pop up with them.

A map of Hanoi, 1925.

Historian Dr. Michael G. Vann wrote in a report, courtesy of Freakonomics, “From the French perspective, the Vietnamese lack of modernity was a central factor in the spread of the disease,” which he suggests further validated the French in their mission. He continued, “French health experts singled out the Chinese as human vectors in the spread of la peste throughout Southeast Asia.” Such racist scapegoating brought a variety of neighborhoods under scrutiny, including Saigon’s Cholon.

Eventually, though, people began to associate the rats with the plague, which marked the beginning of The Great Hanoi Rat Massacre.

Shay Maunz reported for Atlas Obscura that the killings began swiftly and escalated exponentially. For example, on June 21, 1902, an astronomical 20,112 rats were killed in one day.

Due to a disorganized and incomplete paper trail, the details of the rat assassinations are fuzzy. However, it is clear that in the hopes of incentivizing locals to help the government in their war on rodents, they recruited laypeople to join their ranks.

In order to receive the bounty (one cent per rat), all one had to do was present a rat-tail to the municipal office. The French were very pleased with this solution, as they would be absolved from needing to dispose of so many rat corpses.

The Vietnamese, too, were pleased with the arrangement, but not for the same reason. In the beginning, rat-tails poured in as locals slaughtered them by the dozen. Their entrepreneurial spirit took over though, and soon enough, French health officials began to notice a strange phenomenon: tailless rats proliferating in the outskirts of the capital.

Upon further investigation, it became apparent that the Vietnamese were breeding rats specifically to receive cash for their tails. Reports also suggest some people smuggled out-of-town rats into Hanoi.

By 1906, there was an outbreak of plague as a result of the infected rat population. At least 263 people died, most of whom were Vietnamese.

Doumer eventually returned to France. While he had an understandably poor reputation among the Vietnamese, he was lauded as a hero back home and went on to become president.

[Photos via Atlas Obscura]