One of my favorite pastimes during summer holidays was reading through the textbooks for my next school year. History textbooks were the most interesting and fun to read: they were like the Harry Potter of my childhood, in which historical facts are packed in neat little narratives; there are good guys and bad guys; and the good always win.

Fast forward to my secondary and high school years, and I’ve grown out of these stories and the school of thought that history has a black-and-white distinction between good guys and bad guys; that historical events have a chain of three-act stories stringed together. More often than not, the narrators of this version of history were my parents, aunts, uncles, my friend’s parents, my other friend’s parents, and even neighbors.

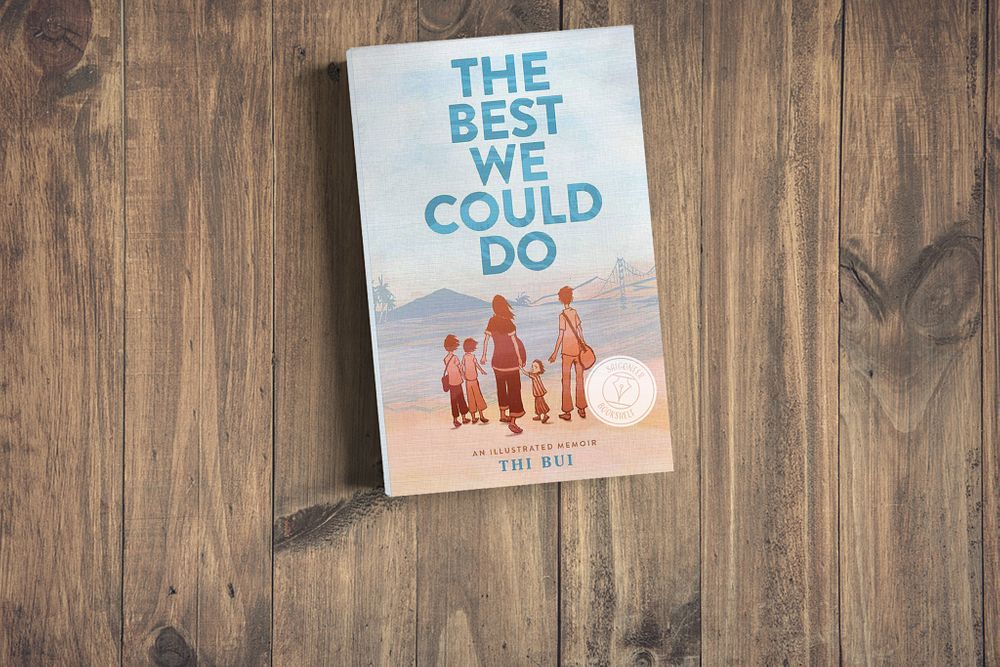

Reading The Best We Could Do, a graphic novel by Vietnamese-American author Thi Bui, evokes strange feelings in me. The illustrated memoir, published in 2017, has become one of the most crucial readings on the Vietnam War and its physical, financial and, most importantly, psychological effects on its victims. Bill Gates even included it, along with Viet-Thanh Nguyen's award-winning novel The Sympathizer, in his list of best books in 2017.

Bui's family decided to leave Saigon in 1978 for the US, and this little detail resonated with me because had my dad decided to do the same, I wouldn't have been born.

Still, her life experience, as shown in the book, also resonates with mine in many ways: there are moments where it's like the pages are chronicling my parents’ story. The book feels like an open secret many have been dying to tell but never got a chance to. Once that secret is out, living in broad daylight and vivid illustrations, it's quite a satisfying experience.

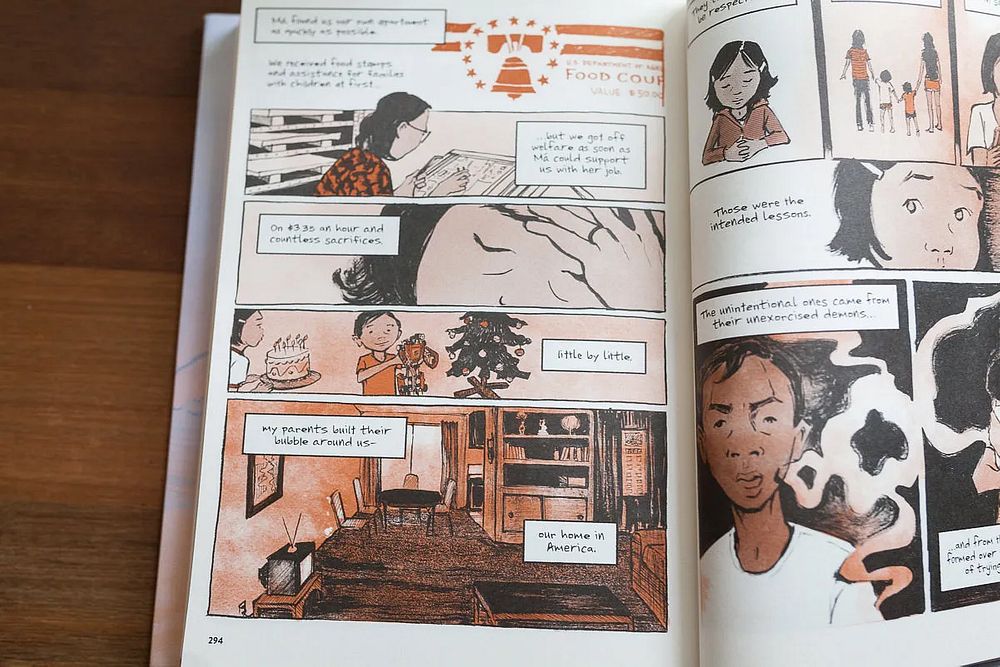

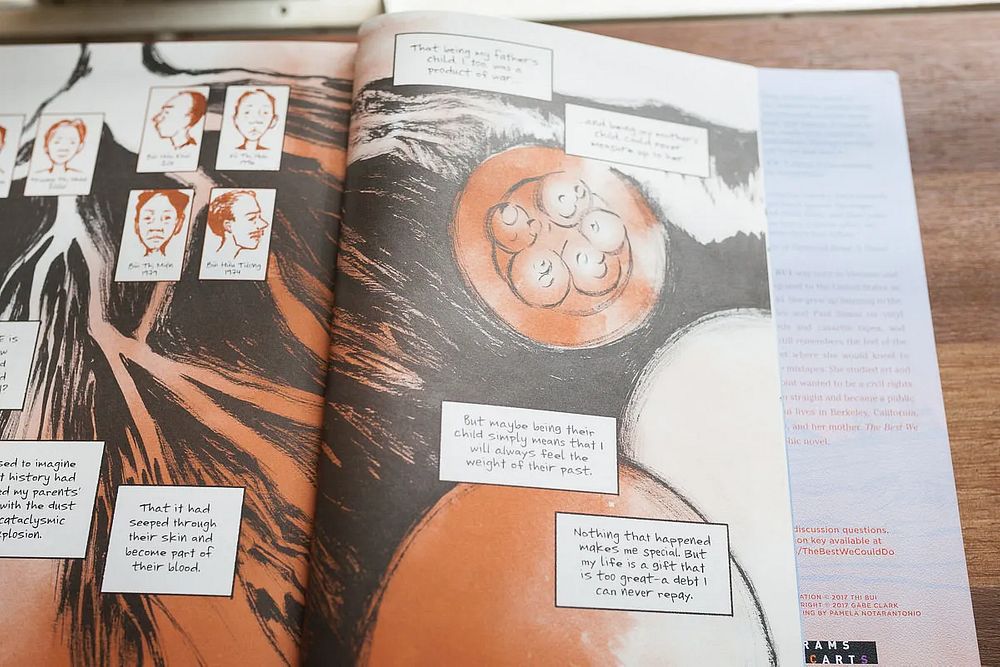

Thi Bui opens her memoir with one of the most intense and vulnerable moments of her life: labor, which is also the name of the first chapter. From there, she traces her family history, going through many major life events: her siblings' births; her parents’ childhood living with French colonialism; her dad’s journey from northern to southern Vietnam after 1954’s partition; the family’s decision to leave Vietnam; the boat journey to Pulau Besar refugee camp in Malaysia; the migration to Indiana; living with their relatives; and the move to California to build a life of their own.

All these personal events are woven into the political turmoil at the time, revealing the complexities of human lives in war-torn conditions. There aren’t simply good guys and bad guys, because according to Bui: “Every casualty in war is someone’s grandmother, grandfather, mother, father, brother, sister, child, lover.”

Bui uses this chessboard as a metaphor for war, or at least how war is perceived from the top. From the other extreme, however, Vietnamese people aren’t pieces on the chessboard, but more like “ants scrambling out of the way of giants, getting just far enough from danger to resume the business of living”.

Moving back and forth between the personal and the political, there are some similarities between Bui’s work and Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi’s memoir about growing up in Iran and witnessing the Iranian revolution. In Persepolis, Satrapi uses black and white to bring out the contrasting symbols and the struggle of living amidst two political extremes.

Bui’s use of color is also symbolic, but takes the form of a monochromatic wash: different shades of orange fill out the book, resembling old blood stains, as a reference to various themes of the memoir: family, national identity, war. This sets a mood for the memoir, and guides our emotions as the color saturation changes through the narratives. The same technique can be seen in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, also a family tale, in which Bechdel uses different shades of blue to heighten the emotional depth of the stories.

Fertility and mortality are also prevalent themes in The Best We Could Do, and Bui ties them together in a way many Vietnamese could relate to. While most of the country was between the edge of life and death, there were flickers of hope for survival and a brighter future. Sacrifices were made, for the better.

At the end of the day, sometimes sacrifices have a dark side. At times, Bui captures how trauma can pass down through generations, and how shadows of the past can never really leave her parents alone, even when they are more than 10,000 kilometers away from the site of grief. In spite of this, Bui ends the memoir on a positive note, looking forward to a different life for her son, a life free of the shadows of a traumatic past.