This poem by Jenna Le appears in issue five of Rambutan Literary and serves as a prime example of the graceful, poignant material that spans its first five issues. Founded in 2016, the magazine features a diverse selection of short stories, poems and artwork from mainland, maritime, and diasporic Southeast Asia.

There is an edible mushroom

endemic to Southeast Asia,

Volvariella volvacea,

whose stipe is grayish white

and softly rounded

like an albino woman’s hips

and whose glossy

chestnut-brown cap

pales toward a tan hemline--

it has a taut, resilient skin,

its pith is

butter-soft,

its flavor

woody and autumnal

and secret--

Vietnamese

settling in California

sometimes plucked

mushrooms from the dirt

and ate them,

believing them to be Volvariella,

but they were Amanita phalloides,

a poisonous fungus

widespread in the West

Turning Rambutan’s digital pages takes readers from a humid Manila office to a privileged Malaysian middle school, Phnom Penh's notorious Tuol Sleng prison and the “deliberate chaos” of a Yangon marketplace. Story subjects include a Singaporean beauty contest whose results open regional divides, the plight of a mentally challenged young man in an impoverished fishing village and a Nawangwulan god who descends from the heavens to marry a mortal Jakarta man. Speakers struggle with sexual identity, racial discrimination and alienation.

The magazine features writers representing Vietnam, Singapore, Malaysia, Myanmar, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, Laos, and the Philippines, in addition to those living abroad who trace their family history to these nations. Considering the diversity of the cultures, traditions, myths and languages of these nations, it is no surprise that the literature traverses a wide range of tones, styles, and subject matter.

A photo by Tian Tran from the series "Burning City," which was inspired by an Ocean Vuong poem and featured in issue four of Rambutan.

Anyone in Vietnam or abroad, whether deep in the trenches of a literature PhD program or casually perusing a library, can attest to a lack of mainstream focus on writers from Southeast Asia. The already undersized “Asian Literature” shelves at bookstores and syllabus sections in school are often filled with older, male writers from more affluent and globally powerful nations. And while Li Po, Ko Un, Haruki Murakami and Jhumpa Lahiri certainly deserve their fame, it's essential to acknowledge the voices that are being ignored.

In an email to Saigoneer, Do Nguyen Mai, Rambutan’s founding executive editor, argues: “We can’t just push for Asian representation in the global literary scene because Asian literature is far from homogeneous. It’s getting better, but a majority of Asian literary publications tend to be geared toward Northeast Asian literary circles, and that’s neither representative of nor necessarily similar to other regional groups in Asia. Additionally, with less regional or ethnic diversity, there’s going to be less class and age diversity.”

Rambutan aims to address these inadequacies while also entertaining, challenging, and educating readers. In the editor’s note to the first issue, Do writes: “Although histories may have spread Southeast Asian peoples across the world, words of our present times can bridge Southeast Asian communities over the globe's vast lands and seas. Rambutan Literary's core mission has always been to serve as an active piece of that bridge, gathering distinct voices of the global Southeast Asian literary community within one shared space.”

The magazine is split into two distinct sections: Branches and Roots. The Roots are dedicated to writers living in mainland and maritime Southeast Asia. Many of the pieces by native writers are concerned with the frantic changes their countries are experiencing in juxtaposition to deep histories and traditions. 'Yawa (Demon),' a story by Jan Angelique Dalisay, for example, is based in a present where evil spirits take the form of school shooters and drug-addled criminals. Some of the works directly challenge traditional values, such as Joyce Cheng’s poem 'Dragon Girls,' which rages against the assumption that “in asia girls cannot be dragons, / instead we are asked to be / phoenixes.”

In contrast Branches, featuring works by members of oversea diaspora, often grapples with an individual’s fraught relationship with their native cultures, such as Linh Le’s poem, 'What Makes me Vietnamese,' or 'Faith Healer' by Ally Ang, in which the speaker exclaims:

When I arrived on these shores

the first thing I learned was that

a brown body is always queer

an immigrant body is always fractured

and I, an immigrant daughter

have inherited this as my gift.

Uprooted, I have tried

to grow on foreign soil

but I am always too alien

an invasive species.

In several of the pieces, characters return to their ancestral homelands, where they experience both cultural coherence and disconnect. In the same way that the Roots describe the difficulty of living in rapidly changing worlds, the Branches articulate the tenuous condition of always existing as an outsider.

Not all the pieces in the issues, however, deal directly with culture and identity, nor do they all focus on deep or somber subjects. Muzakir Xynll, for example, offers a whimsical tale of a trickster participating in a durian eating contest, while Henna O. Yu’s story about a love triangle between young adults could be set in nearly any country. The variety of pieces furthers Do’s argument for the need of diverse voices in Asian literature.

The goal of giving room to marginalized writers helped inform the separation of each issue into Branches and Roots. Do explains: “When writers from Southeast Asia proper see that we designate exactly half of the publication to them, they’re encouraged to submit work because they don’t fear having to compete for space with their diaspora counterparts – and vice versa.” Taking into consideration the needs of each group, the magazine has essentially a double editorial staff - one for Roots and one for Branches, each based in an area of the world their sections represent. Do admits that having such a global team can cause logistical difficulties, but it is ultimately helpful because it enables them to take advantage of the limited resources available in some of the involved countries.

Beyond bringing much-needed attention to Southeast Asian writers, the magazine also succeeds in introducing strong craft. Through sharp language, fresh metaphors, striking descriptions and astute emotional observations, the pieces prove that they are not important solely for what they represent, but stand on their own artistic merits. Lines like “I remember doves, no matter how majestic, are pigeons lacking pigment” from 'Blueprint' by Christine Imperial succeed independent of the magazine’s aim of spotlighting literature from a certain region. Similarly, readers all over the world should find resonance in work like Marylin Tan’s poem 'Oily Blanket Feet,' which includes the following section:

if you feel like a twisted ankle in the back

of my throat it is only because I

am turning into a moth with no proboscis

by virtue of always looking for the moon,

or a glow that stays on longer than two hours

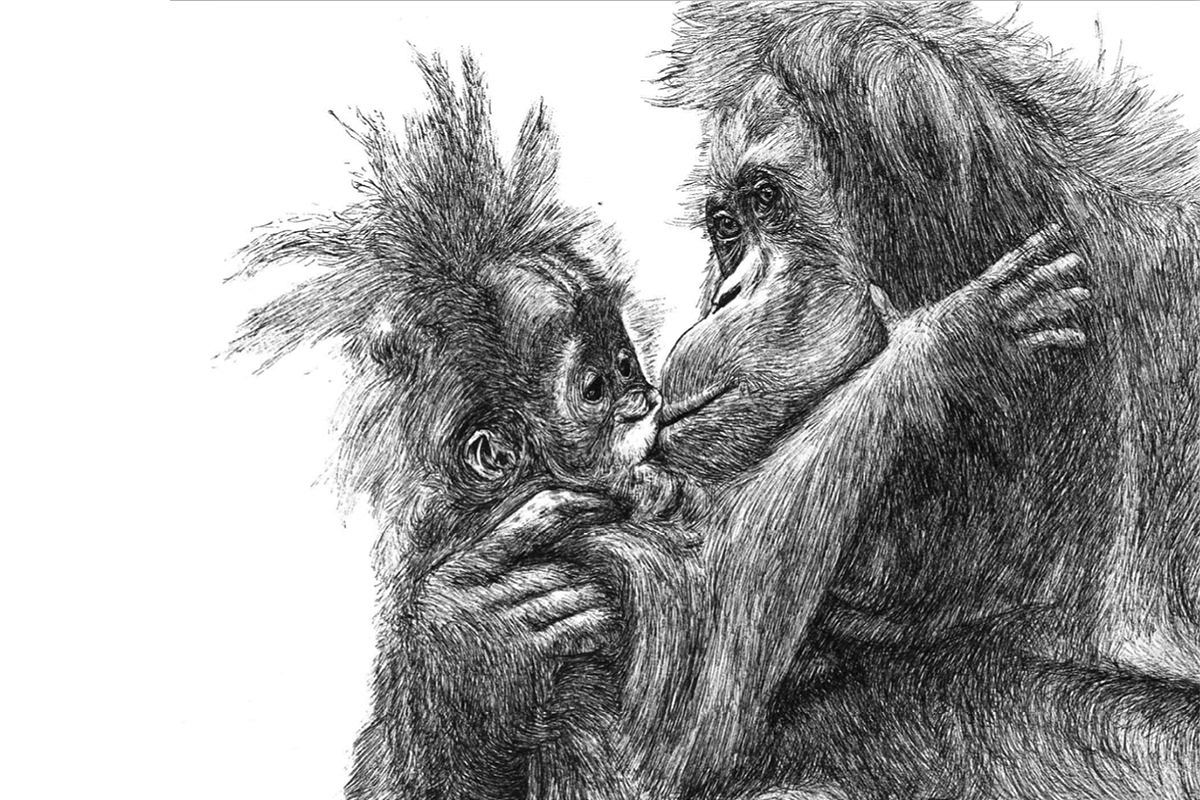

A photo by Nasir Nadzir featured in issue one of Rambutan.

The magazine’s featured art also simultaneously boasts strong craft and cultural consequence. A variety of photos, paintings and illustrations from both Roots and Branches present place, personhood, and politics. Tara Thiagarajan’s painting 'Hamasayse,' for example, depicts a hand gesture used in traditional Bharatanatyam dance. For Thiagarajan, it “symbolizes the grace of a swan, an animal that carries itself with pride regardless of the situations they face, much like the Indian community in Malaysia.”

A vital part of Rambutan’s aim involves motivating young artists. Stefani Tran, the Roots poetry editor based in the Philippines, reveals via email that she while she wants as wide a readership as possible, she especially hopes the work resonates with young readers and writers in Southeast Asia and “for them to hopefully see themselves reflected in the work, and for it to make them proud to be uniquely who they are, and inspire them to go out there and create.”

The need of a platform for emerging Southeast Asian writers lies at the core of the magazine’s founding. Do is a young writer herself, and in 2016 she released her first book of poetry, Ghosts Still Walking, which addresses many of the themes of identity, love, and mythology (her narrative of Vietnam’s origin from the perspective of the Phoenix is especially compelling) present in Rambutan.

Her experiences in finding homes for her poems helped convince her to start the magazine. She explains: “I understand the challenges that come with being a Southeast Asian diaspora writer and feeling like the cultural background from which I’m writing isn’t being respected in publishing. I want to provide opportunities to young and/or Southeast Asian writers all over the world to have their literary voices published and read.”

It shouldn't come as a surprise to anyone that there is little money to be made in creative writing. Rather, outfits like Rambutan are labors of shared love. One benefit of such a setup is they often have an interest in relationship building. Rambutan, for example, includes recommended reading lists of books, magazines, and individual pieces in other publications that focus on Southeast Asia. This is akin to McDonald's including directions to KFC on their receipts, and reflects the collaborative communities literature can help usher into the world.

In addition to its five issues that are all available online for free, Rambutan recently entered the print game. Thanks to a successful crowdfunding campaign, an anthology of their first two years of editions is forthcoming. They are also sponsoring the 2018 Hawker Prize for Southeast Asian Poetry with Sing Lit Station, a Singaporean literary non-profit. You can learn more about the magazine and explore some of the best literature coming out of the region on their website.

Rambutan success reflects the expansion of the region's English-language literature. It joins a growing number of creative magazines focusing on Southeast Asia and Vietnam including Mekong Review, Cha: an Asian Literary Journal, Easlit, and AJAR amongst others.

[Top Illustration by Nasir Nadzir from Rambutan issue one.]