Although the forces of modernization encourage constant progress and leaving behind the pre-modern past, the trails of yesterday never fail to leave our presence.

Old citadels in southern Vietnam are a testament to the above remark. Unlike their northern and central counterparts, which are preserved as heritage sites, citadels built in southern Vietnam no longer have their total physical presence seen and felt by most residents living near them. However, their remnants are still somehow present: the area where the Gia Định Citadel once stood now forms Saigon’s center and encloses government buildings representing the centralization of power; the remainders of a citadel wall in Biên Hòa can still be spotted; and the round vestiges of ancient lives in Bình Phước Province yearn to be studied and explored.

Saigon Citadels

Lũy Bán Bích

Before Saigon had a true fortress or citadel, a city wall called Lũy Bán Bích was erected by the Nguyễn Dynasty general Nguyễn Cửu Đàm to ward off Siamese invasions in 1772, when the city carried the name Gia Định. Though, like much of Saigon’s feudal fabric, no physical remnants of the wall exist, it did help to inform the trajectory of Lý Chính Thắng and Trần Quang Khải streets. The name Lũy Bán Bích is also used for a street in modern Tân Phú District.

The Lũy Bán Bích wall (red line). The map was drawn by Trần Văn Học in 1815 and republished in a 1987 geography book on Saigon. Photo via Wikipedia.

Gia Định Citadel

Saigon’s first true citadel was constructed by 30,000 laborers under the auspices of Nguyễn Phúc Ánh with French technical support in 1790. Meant to act as a temporary royal capital during the Tây Sơn rebellion, the polyhedron-shaped citadel was made of Biên Hòa granite. The fortification — which sat in the middle of today's Lê Thánh Tôn, Nam Kỳ Khởi Nghĩa, Nguyễn Đình Chiểu and Đinh Tiên Hoàng streets — featured five-meter-tall walls and a deep moat, with its main entrance located at the intersection of modern-day Đồng Khởi and Lý Tự Trọng streets.

The citadel had royal housing, military support structures and medical facilities; it acted as an interchange for the Thiên Lý road, which linked the city to the Mekong Delta, Huế and Hanoi.

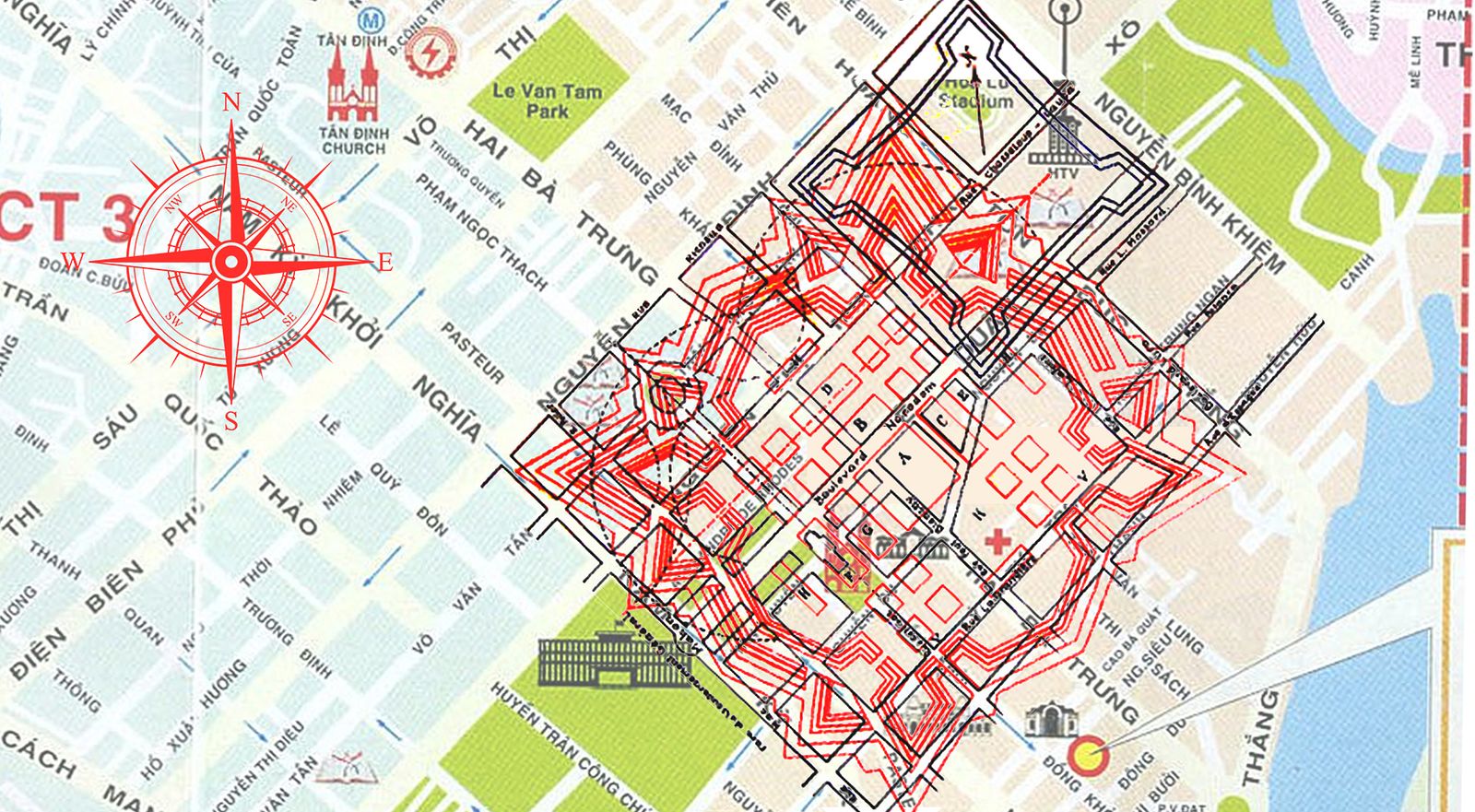

Following the Nguyễn Lord's victory over Tây Sơn rebels, the capital was moved back to Huế, and Gia Định was officially downgraded to a provincial capital. In addition, following a separatist uprisings in the south which occurred in 1832–1835, the grand Gia Định citadel was demolished and replaced by a smaller “Phoenix Citadel” (thành Phụng) constructed in 1837 in the area now bound by Nguyễn Đình Chiểu, Nguyễn Du, Mạc Đĩnh Chi and Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm streets in Vauban style, similar to its predecessor.

The outlines of the Gia Định (in red) and Phoenix (in blue) citadels superimposed over a map of colonial Saigon. Photo via Flickr user manhhai.

The Phoenix Citadel’s lifespan was a short 22 years, as French forces razed the structure in 1859 and replaced it with a military compound (Caserne de l’infanterie), though the area retained its “citadelle” moniker through the colonial period.

French forces attack the Phoenix Citadel. Photo via Wikipedia.

This military complex served as a barracks until 1945, when, under Japanese control, it was used to intern French officers. Following independence from France, the compound was again a historical focal point during the 1963 coup against Ngô Đình Diệm and suffered extensive damage.

The site was then redeveloped with educational and telecommunications facilities and today is occupied by the Hồ Chí Minh City University of Social Sciences and Humanities and the headquarter of local TV network HCMC Television (HTV).

Today, all that ties the location to the long line of citadels and military facilities are the two colonial buildings that stand where the Gia Định citadel’s main gate was.

Gates of the Caserne de l’infanterie seen in the colonial period. The buildings to the left and right are still standing today at the intersection of Lê Duẩn and Đinh Tiên Hoàng streets. Photo via Flickr user manhhai.

Photo by Brandon Coleman.

Biên Hòa Citadel

While Saigon’s citadel might be the most well-known, the Biên Hòa Citadel, also known as the Kèn Citadel or Cựu Citadel, is believed to be the oldest fortress in southern Vietnam. In his work on the history of the area, Biên Hòa Sử Lược, Lê Văn Lương mentions that the citadel was first built by the Chenla Empire during the 15th and 16th centuries using soil.

Under the 15th Minh Mạng ruler in 1834, the citadel was reconstructed by 1,000 laborers who were paid in money and rice for their work, according to the verified records of the Nguyễn Dynasty, Đại Nam Thực Lục. Three years later, under the 18th Minh Mạng ruler, the citadel was renovated using laterite as the main construction material. The citadel had four gates and a flag post and covered an area of 18 hectares, making it the second-largest citadel in southern Vietnam after Gia Định.

An old map illustrating the Biên Hòa Citadel. Photo via Thanh Niên.

The citadel would have retained its original scale if not for the infamous French capture of Biên Hòa, a battle that was part of the Cochinchina Campaign which brought French colonialism to the country. In December 1861, allied French and Spanish troops led by Louis-Adolphe Bonard and Diego Domenech captured Bien Hoa and seized the citadel. The French destroyed most of the structure, and only an eighth of it remained. The east side of the fort was re-purposed for new residential areas, military camps, hospitals and mansions preserved for high-level French officials and military personnel.

Biên Hòa being captured by the French and the Spanish. Painting via Flickr user manhhai.

The only remnants of the Biên Hòa Citadel today are part of the wall made of laterite, two French colonial buildings and several blockhouses located inside the area at 129 Phan Chu Trinh, Quang Vinh Ward. The wall is up to three meter in height. Lê Văn Lương notes that before 1940, two cannons were buried under the main gate. However, when the Japanese captured the area, they were dug up and relocated.

In 2014, the citadel's remnants were renovated by the Biên Hòa Central Fine Arts Company.

Bình Phước’s Round “Citadels”

While most of the fortresses and citadels in southern Vietnam were constructed during the Nguyễn Dynasty, following Vaubanesque military architecture, the mysterious thành tròn in Bình Phước are a different story.

Also known as circular earthworks in archaeology papers, each citadel typically has a diameter of about 200 meters, while larger ones can reach 330 meters. Many of these earthworks have been discovered by archaeologists in Bình Phước and Tây Ninh provinces in Vietnam, and Kampong Cham in Cambodia.

The existence of these round citadels was first mentioned in writing in 1930 in a volume of the Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient. The text mentions the discovery of two earthworks that the author called forteresses moï, or mọi fortress (mọi is a derogatory term to refer to people living in the highlands and Khmer people), in two areas of Quản Lợi and Lộc Ninh, which housed two huge rubber plantations in Bình Phước at the time. According to Nguyễn Khải Quỳnh, by 1959, another 11 sites were discovered by Louis Malleret, a French archaeologist at the French School of The Far East. More sites were discovered and studied by Vietnamese archaeologists after 1975, while the ones in Cambodia also received attention in the country.

A typical thành tròn has two walls with the same center, separated by a ditch. However, others only have either one outer wall or inner wall. Underneath the inner platform of these sites, stone tools, weapons and ceramics were found.

A 3D image of the Hourn Khim circular earthwork in Cambodia. Photo via Memot Center for Archeology.

Archaeologists have yet to reach a conclusion on the function of these circular earthworks. The existence of artifacts in the inner platform indicates they might have been a habitation area of an ancient community. However, no artifacts have been found in the ditches of these thành tròn. Some have argued that the ditches were used as a water reservoir, but this theory doesn't make sense to some, as red soil is very permeable. Some argue that besides habitation, the sites could have also provided protection against enemies and wild animals, although some of the ditches are not deep enough to serve as a moat. Another theory is that the ditches served as a place to keep animals.

The outline of some identified circular earthwork sites in Bình Phước can be spotted via Google Maps below:

Long Hà Circular Earthwork 3.

Lộc Ninh Circular Earthwork.

Read the second part of Unearthed, our series on Vietnam's past citadels here.