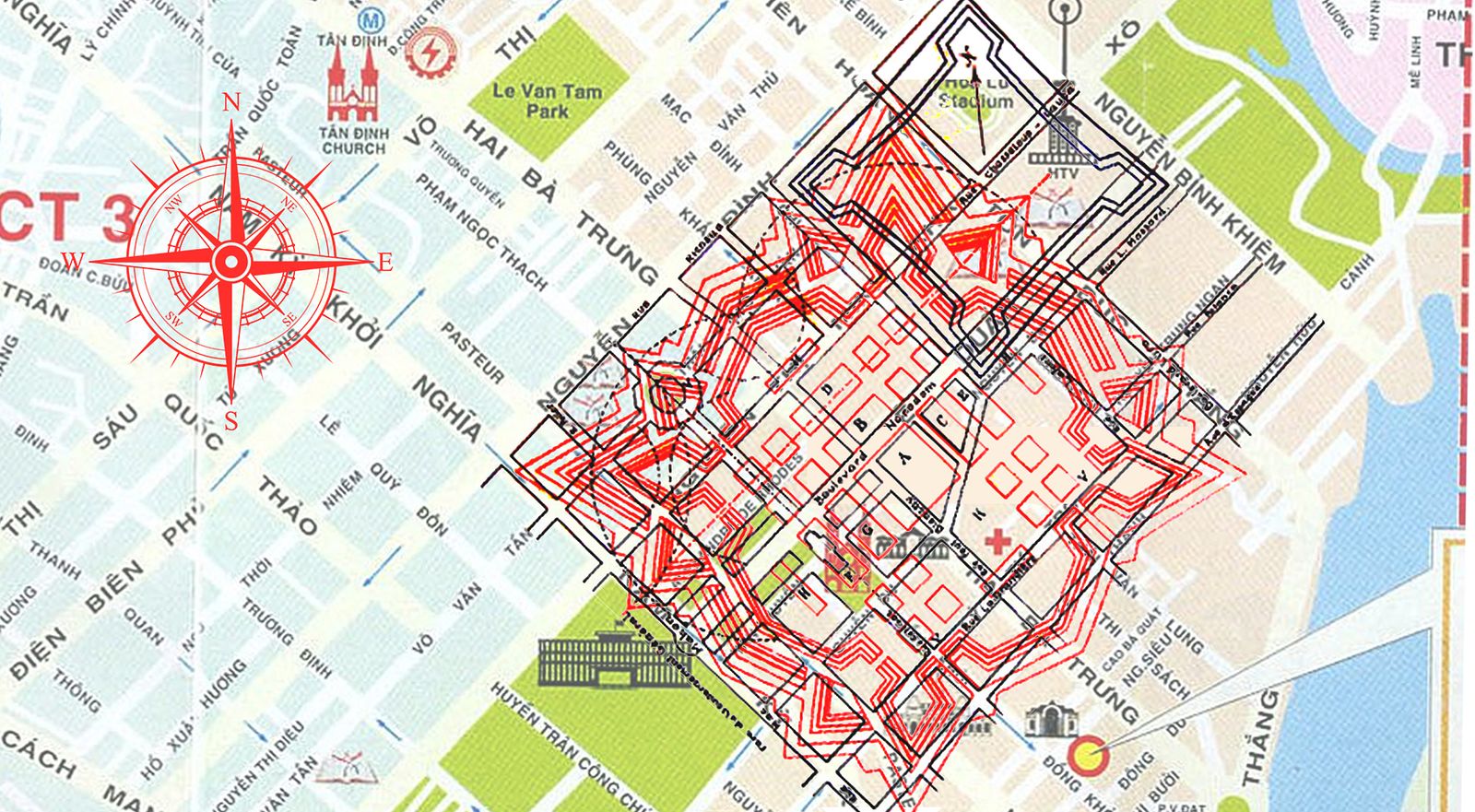

In our previous article on Vietnam’s southern citadels, we covered a mix of ancient structures and those constructed just before the dawn of French colonization of Indochina. In particular, we focused on Gia Định Citadel, a hulking structure that once stood in what would become Saigon’s city center. Undertaking a similar exercise for Vietnam’s central and northern regions is less practical, given the sheer quantity and variety of citadels in those regions. So, for the second part of our citadel series, we instead will focus on a unifying feature across such fortifications — Vauban architecture.

The style is the brainchild of Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, a Frenchman described as one of the most prominent and influential military strategists during the reign of Louis XIV. His designs, strategies, and principles remained in use until the early 20th century. The development of Vauban architecture emerged against the backdrop of the turbulent geo-political and religious strife which engulfed Europe in the 17th century, which involved major siege warfare. At this point in military history, it was accepted that even the strongest fortifications would eventually fall, so their ultimate function was to absorb the attacker's energy to take the wind out of the larger offensive at hand.

The fortress Neuf-Brisach in France, Vauban's final work and the culmination of his "Third System." Completed in the early 18th century after Vauban’s death. Photo via Forte Cultura.

With this in mind, Vauban improved upon previous designs by using specific shapes, including pentagonal and hexagonal outer walls and layers in his fortifications. They would sometimes include residential and commercial districts within a fortification’s walls. Therefore, Vauban theory went beyond simply military strategy, architecture and construction, but also extended to civil engineering and economic and social organization.

Fortifications of this style which, per UNESCO, “bears witness to the peak of classic bastioned fortification, typical of western military architecture of modern times.” Some of them endure long after Vauban’s death in 1707. During his prolific career, he personally oversaw the construction of 300 such structures across the globe, from the Americas to what is now Vietnam, where French engineers helped construct such fortifications for the Nguyễn Dynasty.

Pigneau de Béhaine, painted by Maupérin during his 1787 trip to Paris with Crown Prince Cảnh, on display at the Paris Foreign Missions Society. Image via Wikipedia.

According to a research paper by Frederic Mantienne, the influx of European military technology coming in to Vietnam arose out of the need to overpower the Tay Son army after their victory against the Nguyen dynasty in 1773. Four years later, Nguyễn Ánh, the Nguyễn family survivor, became acquainted with a French missionary named Pierre Pigneaux de Béhaine — whose mausoleum was replaced by a roundabout near Tân Sơn Nhất Airport in 1983, better known by the name Lăng Cha Cả — more commonly known in Vietnam through his Vietnamese name Bá Đa Lộc. Bá Đa Lộc became Nguyễn Ánh’s advisor and the individual that persuaded him to seek military support from France, a major reason for Nguyễn Ánh’s rise to power.

Five years after Nguyễn Ánh proclaimed himself king in 1780, Bá Đa Lộc was sent to Pondicherry, in modern India, and then France to lobby for French military assistance for the Nguyễn army. The trip resulted in the Versailles military treaty (Traité de Versailles de 1787) between France and Cochinchina. While the treaty ultimately wasn’t enacted, Bá Đa Lộc managed to create enough French commercial interest to bring ammunition and a number of French naval officers, including two army specialists, to Cochinchina. These specialists were trained in fortification and artillery techniques.

With this new assistance, Nguyễn Ánh, who went by Emperor Gia Long at that point, ordered the first citadel to be built using the Vauban technique — Saigon’s Gia Định. According to Mantienne, French engineer Theodore Le Brun was tasked with the design for the citadel, and Oliver de Puymanel and the king would oversee the construction.

The second and last citadel with French involvement in Vietnam was Diên Khánh, located in Khánh Hòa Province near Nha Trang, which was built in 1793 after Nguyễn A!nh succeeded in leading a campaign there against the Tây Sơn. It was constructed under the command of Bá Đa Lộc, Puymanel and Gia Long’s eldest son, Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh.

Portraits of Gia Long. Images via Disan Vietnam.

The Diên Khánh Citadel witnessed many battles between the Nguyễn army and the Tây Sơn. One of particular importance is a 1795 attack on the citadel led by Tây Sơn General Trần Quang Diệu. The Tây Sơn army managed to win the battle, however, they could not take the citadel. In this way, Diên Khánh proved to the Nguyen leaders the effectiveness of Vauban fortifications in their tactics.

Left: Diên Khánh citadel plans. Image via Wikipedia. Right: Present-day Diên Khánh Citadel in Khánh Hòa Province. Image via Google Maps.

French scholarship points to Oliver de Puymanel as the mastermind behind the Diên Khánh Citadel, and that it was Le Brun and Puymandel who also designed and built the Saigon citadel. However, Vietnamese intellectuals continue to debate Puymanel’s roles in the construction. Some, such as critic and journalist Thụy Khuê, in her collection of research essays, suggests that French colonial scholars might have exaggerated the two Frenchmen’s importance in the construction thanks to a reliance on flimsy sources. The inflated claims were published in Vietnamese texts as facts and became a myth.

Regardless of whether it was via direct or indirect transfer of French technologies, there is no denying that the Vauban style made its way into the design of fortifications in Vietnam and continued to exist and influenced fortifications under Gia Long, Minh Mạng and Thiệu Trị.

The third citadel that has Vauban influence after Diên Khánh was the famous Huế imperial city, which was built in 1802 when Gia Long (Nguyễn Ánh) moved the capital to Huế. From 1802 until 1844, 32 new citadels with a design resembling Vauban architecture were built in Vietnam, their placement and location obeying feng shui principles. Some also featured details reflecting traditional Vietnamese architecture elements.

Under the rule of the Gia Long emperors, many citadels were polygonal, with a few exceptions. In the north, Bắc Ninh Citadel was the first fortification to be built with a hexagonal shape. The citadel was built in 1805 under Gia Long using soil. Under the sixth Minh Mạng ruler, the citadel was rebuilt using laterite (a metal-rich clay), and in 1841 under Emperor Thiệu Trị, the fortification was rebuilt again with bricks.

Left: Turcos and fusiliers-marins at Bắc Ninh, 12 March 1884. Image via Wikipedia. Right: Present-day Bắc Ninh Citadel. Image via Google Maps.

The Hạc Thành Citadel, or Thọ Hạc, is another example of a hexagonal citadel. It was built in 1804 and marks the birth of Thanh Hóa Province as the geographical area as we know today.

Right: Hạc Thành Citadel seen on a French 1909 map. Image via Wikipedia. Left: Present-day Hạc Thành Citadel. Image via Google Maps.

In his paper, Mantienne mentioned that pentagonal citadels, a hallmark of the Vauban style, also appeared during Gia Long’s rule, including ones built in Quảng Ngãi and Hải Dương in 1807. However it’s unclear if this is indeed true, as the remaining outline of the Quảng Ngãi Citadel today has a square form with eight protruding corners. As for the citadel in Hải Dương, Vietnamese sources suggest it had a hexagonal shape instead. While the citadel in Hải Dương was left in ruin by French colonialists and the Second Indochina War, a search on Google Maps reveals its remaining outline.

Left: Present-day Quảng Ngãi Citadel. Image via Google Maps. Right: Present-day Hải Dương Citadel. Image via Google Maps.

Citadels built under Minh Mạng emperors no longer saw an abundance of polygonal shapes. Instead, square or rectangular forts were used more often. While this may seem like a simplification of the design of earlier citadels due to lack of French assistance, Mantienne and Cong Phuong Khuong argue that these citadels followed some of the latest fortification innovations in Europe at the time.

An example of a citadel that exemplifies Minh Mạng-era fortifications is the Đồng Hới Citadel, which comes in a generic quadrangle shape with an additional four corners, each sticking out from the center of each side. The citadel was originally built by Emperor Gia Long using soil in 1812. However, in 1824, under the reign of Minh Mạng, the citadel was redesigned and rebuilt using bricks. It is located in Đồng Hới, Quảng Bình Province.

Present-day Đồng Hới Citadel. Image via Google Maps.

Another example of a citadel that underwent reconstruction during the Minh Mạng era is the old Quảng Trị Citadel, located in Quảng Trị Province. It was first constructed in 1809 with soil and rebuilt using bricks in 1837. Square in shape, with four bastions extending from four corners, the citadel shape is more similar to some inner layers of Vauban structures in France, such as the fort of Saint-Martin-de-Ré built by Vauban himself in 1681. Under French colonial rule, a prison, along with other buildings, were erected inside the citadel (seen in map below). Today, the citadel is known as a “cemetery without headstones,” due to the death toll during a 1972 battle that occurred there.

Left: Quảng Trị Citadel seen on a 1889 French map. Right: Present-day Quảng Trị Citadel. Image via Google Maps.

New citadels built under Minh Mạng existed too, such as the Sơn Tây Citadel. Its square shape, with four round protrusions on four sides, differs slightly from others. It was one of the earliest built after Minh Mạng became emperor in 1820. Erected in 1822 with laterite and located in Sơn Tây, 40 kilometers outside of Hanoi, the structure is currently known for its octagonal 18-meter high flag post, which also doubles as an observation center. On the top of the post, a transmitter was installed for emergency communication.

Left: Sơn Tây Citadel seen on an old British map. Right: Present-day Sơn Tây Citadel. Image via Google Maps.

While Gia Long and Minh Mạng hold an impressive Vauban fortification portfolio, only one citadel is credited to Emperor Thiệu Trị, perhaps because of his relatively short reign of just six years, from 1841 to 1847. This is compared to Gia Long’s 18 years of rule (1802–1820) and Minh Mạng’s 21-year rule (1820–1840). The citadel in question is located in Tuyên Quang Province. Though not originally built under Thiệu Trị, the emperor conducted a massive reconstruction of the structure, which was first erected during the Mạc dynasty in the late 16th century with a square shape.

Thiệu Trị was also involved in another large reconstruction project at Điện Hải Citadel in Đà Nẵng. According to historian Tim Doling, it was first built by Gia Long as a fortress. The Vauban architectural elements spotted in the remains of the citadel today are courtesy of Thiệu Trị’s reconstruction in 1847, which is also the year that he died.

Left: The current entrance to Điện Hải Citadel. Photo via People's Army Newspaper. Right: Present-day Điện Hải Citadel. Image via Google Maps.

A deeper understanding of these structures, some of which have faded from view, and others prominent symbols of Vietnam’s heritage, gives one a deeper appreciation of their roles in the country’s history. They also show that many of humanity’s best ideas often migrate, across constructs including borders and time, like humans themselves.

Read the first part of Unearthed, our series on Vietnam's past citadels here.